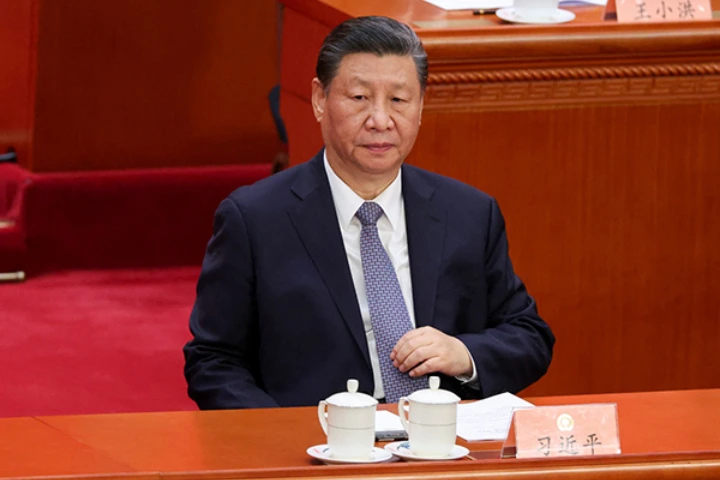

Chairman Xi Jinping ascended the highest throne of the Chinese political hierarchy nearly 14 years ago. His leadership was initially almost faultless from China’s point of view, as the nation prospered economically, diplomatically and militarily. However, Xi’s style of governance has initiated huge concerns at home and abroad, and his aura of untouchability has been tarnished by a confluence of factors.

In years past, Xi assessed that China was enjoying a “period of strategic opportunity,” allowing him to focus on domestic development. However, Xi reported to the 20th Party Congress in 2022 that the nation had entered a period in which “strategic opportunities coexist with risks and challenges, and uncertain and unpredictable factors are rising”.

Professor Steve Tsang, Director of the SOAS China Institute at SOAS University of London, told ANI of some of the challenges currently facing Xi.

“The biggest challenge China faces in governance terms is the concentration of power in Xi’s hands, as the end of the zero-COVID policy followed almost immediately the 20th Party Congress at which Xi amassed even greater power in his own hands, with no one in the new leadership lineup who can speak frankly to advise him to avoid predictable mistakes.”

Professor Tsang added, “Issues like a weak economy, bursting of the property bubble, local government debts and deteriorating relations with the West are challenging, but not necessarily unsurmountable, if the government can get its act together. With collective leadership replaced by strongman rule, it now all depends on Xi understanding them and getting the right policies, and he is just not getting it right.”

Xi is interested only in top-down control, but this approach conflicts with private-sector, demand-driven economic growth. One of Xi’s solutions amounts to epithets for the people to prepare for “struggle”. China’s leader refuses to compromise on his vision for the nation, and so he has begun shutting out the world and shoring up things at home.

Professor Tsang, co-author of the book ‘The Political Thought of Xi Jinping’ published earlier this year, observed: “Most of the key challenges are structural and would have been there whoever might have been the leader in China, such as an unbalanced economy and the transformation of a demographic bonus to a demographic deficit, etc. But Xi’s policies have made most of them worse.”

The Hong Kong-born academic gave the following examples. “He pricked the property bubble. His anti-welfare approach makes it politically impossible to stimulate domestic consumption. His cutting down of tall poppies in the private tech sector has reduced its vitality.”

Economic data from China has been gradually disappearing for a number of years as the government tightens control and as Xi puts ideology before economic growth. Whether exports, youth unemployment rates or cement production, such diverse figures have all vanished. The property market makes up 30 per cent of China’s GDP, but the government stopped releasing data such as land sales or consumer confidence too.

Furthermore, figures are suspicious. As one example, official export data from the China Customs Bureau is diverging noticeably from that of import data in other countries. In other words, China is overstating how much it is exporting.

Indeed, some are describing official data as “bordering on useless,” and Xi appears to think that keeping everybody in the dark will help maintain power and social stability in an increasingly closed society. The Annual Government Work Report at last month’s National People’s Congress (NPC) still promised 5 per cent GDP growth, but again such figures are becoming untrustworthy.

The sectors struggling most are China’s property market, indebted local governments and the banking system, as the COVID-19 rebound stalls. A sizeable proportion of China’s 400 million middle class have bought unfinished apartments, with dim prospects of them ever being finished. Property developer Evergrande, for instance, owes debts of RMB2.5 trillion. Despite Xi’s 2020 pronouncement that poverty had been eliminated in China, actually 43 per cent of the population – around 600 million people – live on less than USD150 per month. Even though the government recently raised monthly benefits for the elderly by 19 per cent, it still only amounts to RMB123.

Doctor Willy Wo-Lap Lam, Senior Fellow at The Jamestown Foundation think-tank in the USA, noted: “The annual plenary session of the NPC…should have seen the articulation of a clear-cut direction to tackle the dire economic situation. Instead, the focus has turned to how supreme leader Xi Jinping is exercising his power. Evidence has continued to emerge that the 71-year-old General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and commander-in-chief is more interested in consolidating his own power and stoking the flames of nationalism than reintroducing market-oriented policies to remedy the nation’s financial malaise.”

Xi continues to bend the rules and conventions in order to solidify power. For example, Xi canceled the end-of-NPC press conference, an event held for nearly 30 years. It is the only time where senior CCP cadre faces the media, and Xi has now spurned this arrangement going forward.

Doctor Lam commented: “This reduces the premier’s ability to cultivate a personal identity independent of Xi, as well as limiting the transparency and accountability – to the extent that it exists – of the government.”

Indeed, this is just one more instance of Xi sidelining the decision-making power of the government. In 1987 Deng Xiaoping established separation of party and government so that the excesses of another Mao Zedong could be avoided. Yet the political hierarchy has meekly accepted Xi’s reversal of that policy. Indeed, the NPC even endorsed Xi’s revision of the State Council Organic Law so that the State Council’s principal task is merely to implement policies and laws thought up by Xi as party leader.

In other words, the NPC has become even more a rubber-stamp parliament than before.

Doctor Lam further noted: “Xi has in the past few months repeatedly violated party practices. The CCP leadership postponing the Third Plenum of the 20th Central Committee indefinitely, which was expected to be held at the end of 2023, is a notable example. The party’s Charter also points out that changes in the composition of the Central Military Commission could only be effectuated in a plenum. Yet disgraced former defense minister Li Shangfu was dropped from party documentation last month. And contrary to conventional processes, not a single word was given to acknowledge or explain the disappearance of a dozen-odd generals as members of the NPC and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference.”

Is Xi grooming successors, or is there any indication that Xi might pass on the baton?

Some, for example, have highlighted the meteoric rise of Hu Haifeng, son of former Chinese leader Hu Jintao. Earlier this year he was promoted to the vice-ministerial rank of deputy civil affairs minister. This has occurred, even as his ageing father remains almost invisible after his chilling removal from an NPC meeting in October 2022.

However, Professor Tsang remarked, “There is no successor lined up or in sight. Xi Jinping Thought is committed to promoting one leader, and Xi has shown no inclination to anoint a successor. He is not seeing a need for a successor for a long time.”

Significantly, Xi is carefully controlling the power of his subordinates and promoting his favorites. Premier Li Qiang and Executive Vice-Premier Ding Xuexiang – the State Council’s top two people – have not received major portfolios. Furthermore, Vice-Premier He Lifeng, who directs the Office of the Central Financial and Economic Affairs Commission, seemed to gain his position through his acquaintance with Xi in his Fujian years in the 1980s-1990s rather than through any inherent technocratic expertise.

Asked whether there are any hints of opposition in the CCP to Xi’s leadership style, Professor Tsang said, “There is plenty of unhappiness about his approach and the direction of travel he has set for China, but no organised opposition of any kind. Xi’s first priority has always been one of eliminating internal opposition so his hold to power is tight, and he is still successful so far.”

As Xi’s difficulties on the home front multiply, some analysts are concerned that Beijing will lash out externally to deflect the populace’s attention. US President Joe Biden described China’s economic woes as a “ticking time bomb” last August, suggesting that its leaders might “do bad things”. And analysts such as Richard Haass, former president of the Council on Foreign Relations, have argued that China could exhibit “even more aggressive nationalism” to cement its legitimacy and accelerate unification with Taiwan.

“Diversionary wars” are designed to boost the status of leaders wanting to stay in power, as their people tend to rally around the flag. However, with the possible exception of the battle with Soviet forces for the disputed island of Zhenbao/Damasky in 1969, there is no real track record of modern China starting a conflict to distract the population and bolster support.

Perhaps more likely in China’s case is the country lashing out at others to show its strength and to deter others from taking advantage of any perceived weaknesses. This is what it did when it attacked India along their disputed border in 1962, to show its resolve and deter future challenges.

Similarly, China reacted with a display of force when the Japanese government purchased three Senkaku/Diaoyu islands in 2012.

Even in 1989, during the tensions that climaxed with the Tiananmen Square Massacre, the CCP preferred to use violence against its own citizens and was relatively conciliatory afterwards to help stabilise things abroad.

Of course, China under Xi is a very different prospect. Nonetheless, M Taylor Fravel, Director of the Security Studies Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, argues a diversionary war is rather a mythical prospect for Beijing.

He noted, “China’s lack of diversionary behaviour also highlights a flaw in the logic of waging a diversionary war. According to such a rationale, leaders looking to boost their popular support should start a conflict with a stronger adversary – because prevailing over a worthy opponent highlights a leader’s acumen – or over a nationalist issue that the public cares greatly about. Yet both are dangerous gambits because, if leaders initiate a diversionary crisis or war that fails to produce the desired results, they risk expediting the collapse of their government.”

Fravel continued: “In other words, it is difficult for a leader to find a target that carries minimal risk but can also boost popular support. China could easily start and win a conflict with the Philippines over the disputed Second Thomas Shoal in the South China Sea, where Manila beached a naval vessel in the late 1990s to underscore Philippine sovereignty over the reef. Yet the Chinese public would likely be unimpressed – they would expect China to defeat a much weaker state. And although the Chinese public views Taiwan as a much more salient issue, a conflict over the island would be costly and the result uncertain. The worst outcome for any Chinese leader would be to try to take the island but fail, which induces caution.”

Fravel concluded: “If China’s economic woes get worse, its leaders will probably become more sensitive to perceived external challenges, especially on issues such as Taiwan. Increased pressure on China could easily backfire and motivate Beijing to become more aggressive in order to demonstrate its resolve to other states despite its internal difficulties. In times of domestic unrest, China may lash out, but that reflects the logic of deterrence, not diversion.”

One thing is certain, however, and it is that Xi is facing unprecedented challenges at home and overseas. After amassing so much power and centralising political authority, it is difficult to see him relinquishing it or permitting others to steer him on a different course.

As Doctor Lam of The Jamestown Foundation concluded, “Irrespective of the diagnosis, so long as Xi keeps arrogating all powers and responsibilities to himself, the long-term outlook on the political, economic and diplomatic fronts will not improve.”