As NASA wants to send humans to Mars as early as the 2030s, a new study has found that astronauts in crewed missions to the Red Planet could misread vital emotional cues.

A study published in the journal Frontiers in Physiology, says, in testing, research participants were more likely to identify facial expressions as angry and less likely as happy or neutral.

The research showed that living for nearly two months in simulated weightlessness has a modest but widespread negative effect on cognitive performance that may not be counteracted by short periods of artificial gravity.

While cognitive speed on most tests initially declined but then remained unchanged over time in simulated microgravity, emotion recognition speed continued to worsen.

"Astronauts on long space missions, very much like our research participants, will spend extended durations in microgravity, confined to a small space with few other astronauts," said Mathias Basner, Professor at the University of Pennsylvania's Perelman School of Medicine in the US.

Basner went on to add: "The astronauts' ability to correctly 'read' each other's emotional expressions will be of paramount importance for effective teamwork and mission success. Our findings suggest that their ability to do this may be impaired over time."

Previous studies have shown microgravity causes structural changes in the brain, but it is not fully understood how this translates to changes in behaviour.

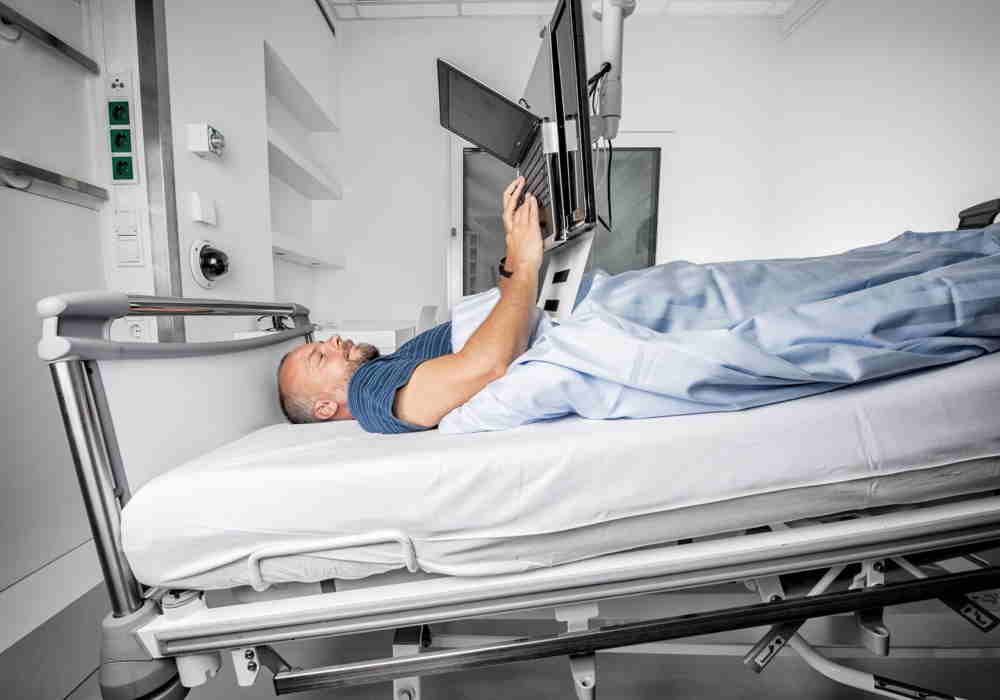

Head-down bed rest at a slight 6-degree angle is the standard way of simulating the effects of microgravity on Earth.

Participants for this research were kept in that position for nearly two months.

"Participants regularly completed 10 cognitive tests relevant to spaceflight that were specifically designed for astronauts, such as spatial orientation, memory, risk taking and emotion recognition," explained Basner.

"The main goal was to find out whether artificial gravity for 30 minutes each day — either continuously or in six 5-minute bouts — could prevent the negative consequences caused by decreased mobility and head-ward movement of body fluids that are inherent to microgravity experienced in spaceflight."

Artificial gravity countermeasures consisted of spinning participants on a centrifuge.

Positioned like an arm on a clock with their head in the middle, the participants were spun round at the speed of 1 revolution around the 'clock' every two seconds.

"There are two ways to produce gravity in spaceflight: rotate the whole spacecraft/station, which is expensive, or just rotate the astronaut. The centrifuge could be self-powered, doubling up as an opportunity for exercise," said Alexander Stahn, the study’s co-author and Research Assistant Professor at the University of Pennsylvania's Perelman School of Medicine.

"Unfortunately, we found that the artificial gravity countermeasures in our study did not have the desired benefits. We are currently performing additional analyses using functional brain imaging to identify the neural basis of the effects observed in the present study."

In the future, the team plans to test longer duration artificial gravity countermeasures and to vary the degree of social isolation.

(With inputs from IANS)