The Afghanistan-Pakistan dispute over the Durand Line has taken centre- stage yet again. Facing prospects of high-octane street protests Pakistan's National Security Adviser Moeed Yusuf has dropped his plans of leading a high-level inter-ministerial delegation to Kabul on January 18 for two-day talks on the Durand Line dispute and the humanitarian crisis exploding in Afghanistan!

In the last week of December 2021, videos showing Taliban fighters removing Pakistan’s border fencing appeared on social media. Taliban commanders were seen threatening Pakistani soldiers against pursuing construction of the border fence. Various spokespersons and Taliban Commanders described the Durand Line border fence as “illegal”, and resolved to “not allow the fencing anytime, in any form”.

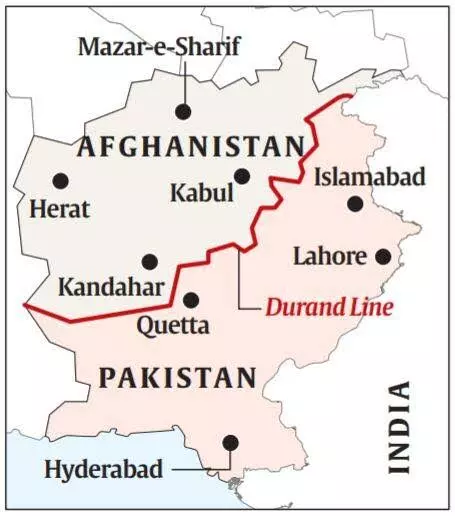

What is the Durand Line? Henry Mortimer Durand, Foreign Secretary of British India from 1884 to 1894 left behind two legacies in India and Pakistan. One, the popular Durand Cup Football Tournament in India that started in 1888, and the other the Durand Line established in 1893, in the Hindukush, running through the tribal lands between Afghanistan and British India. The Durand line was the outcome of an agreement that Henry Mortimer Durand had induced the Afghan ruler Amir Abdur Rahman to sign in November 1893, delineating the sphere of influence between British India and Afghanistan.

After the Third Anglo Afghan War in 1919, between Afghanistan and Britain, an armistice was signed on 8th August 1919. Britain officially relinquished control of Afghanistan’s foreign policy, and declared Afghanistan as an independent nation, with the border between Afghanistan and British India running along the Durand line. In 1947 at the time of India’s independence and partition, Afghanistan refused to accept the Durand Line as the international border, as various tribes including the Pashtun & Baloch, inhabited the land spread across the line.

Daoud Mohammad Khan, the first President of the Republic of Afghanistan, who was also the Royal Prime Minister from 1953 to 1963, was a great proponent of uniting Pashtun areas, for a united and strong Afghanistan. His relations with Pakistan were evidently strained. In 1960 – 1961, consequent to some incursions by Afghans, Pakistan stopped all trade movements across the Afghanistan – Pakistan border. The economic impact of the trade blockade on Afghanistan, was compelling enough for Afghanistan’s King Zahir Shah to seek Daoud Mohammad’s resignation as Prime Minister. In March 1963, King Zahir Shah took charge of affairs himself and got relations with Pakistan on an even keel.

On 17 Jul 1973, Daoud Mohammad Khan overthrew Zahir Shah, ending two centuries of monarchy, and created the Republic of Afghanistan. He thus became the President of the Republic. Daoud Mohammad’s policy against Pakistan, was much appreciated by the Soviet Union since Pakistan was actively allying with both the USA and China.

Despite Afghanistan’s hard-line policy, Pakistan’s ISI stayed active in Afghanistan since its early days. In 1974, they undertook a covert operation to extricate their agents Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, Ahmed Shah Massoud, and Burhanuddin Rabbani, from Kabul to Peshawar. By 1975, Pakistan started running a proxy war in different provinces of Afghanistan to overthrow Daoud. The combined consequence of dependence on trade routes and the proxy war, forced Daoud to give in to recognising the Durand line as the border in 1976.

Through the 1980s, Pakistan adopted a two-pronged strategy to deflect the Pashtunistan movement. First – mainstreaming the Pashtuns by bringing them into politics, military, and civil services of Pakistan; and second – radicalising young Pashtuns brainwashing them into fighting the US backed Jihad against Soviet Union in Afghanistan.

After the 9/11 terrorist attacks on USA, Pakistan ostensibly joined the global war on terror in Afghanistan. Buoyed by the turn of events, President Pervez Musharraf tried to exploit the opportunity to construct a border fence along the Durand line. While the fence was apparently meant to curb infiltration, the underlying intention was to demarcate the border, thus helping in defeating the Pashtunistan movement and Baloch nationalism. The plan was dropped due to heavy resistance from Pakistan’s Pashtun political parties and Afghanistan.

By late 2000s Pakistan undertook a series of military operations against their own creation – the Taliban, in the tribal areas bordering Afghanistan. Eventually in 2017, Pakistan started constructing the two-layer fence along the entire length of its borders with Afghanistan. In the past five years, Pakistan claims to have completed nearly 90% of the fencing, 67 new wings of Frontier Corps Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa have been established to strengthen border security.

Pakistan sees multiple advantages of fencing and strengthening the Durand Line; first – it demarcates this long-disputed border, enabling better border management and release of forces for the East against India; second – it helps in curtailing the Pashtunistan movement and Baloch nationalism; third – complements Pakistan’s endeavour to divide and decimate the Tehrik e Taliban Pakistan (TTP); fourth – tightens Pakistan Army’s control over the narcotics trade from Afghanistan for generating revenues to fund terrorism against India, manipulate domestic politics in Pakistan, and feed the private coffers of Pakistan’s military elite and their allies; and fifth – control the flow of international aid into Afghanistan, thus securing the ability to divert funds.

Addiction to narcotics, and addiction to the narcotics revenue, also drives the conflict between Pakistan Army – TTP – Taliban. The winner gets to control the narcotics trade from Afghanistan. According to the UNODC November 2021 report, Afghanistan accounted for 85 per cent of global opium production in 2020, and the areas bordering Pakistan, remained Afghanistan’s major opium producing region, accounting for 71 per cent of total opium production in Afghanistan. Besides using narcotics-revenue to fund terrorism against India, Pakistan has been pushing drugs into India to destabilise the situation in the border states.

Soon after the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan in August last year, Pakistan actively intervened to position a friendly Haqqani network dominated Government in Kabul. Head of the Haqqani network – Sirajuddin Haqqani was appointed as Afghanistan’s Acting Interior Minister. Other Haqqani members given key appointments include Mullah Taj Mir Jawad – Deputy Chief Intelligence, Khalil ur-Rahman Haqqani, Minister for Refugees, Abdul Baqi Haqqani – Minister for Communication, and Najeebullah Haqqani – Education Minister.

Pakistan has been trying to project the current ruling regime – Taliban 2.0, as different from the 1996 version – Taliban 1.0: moderate, liberal, and inclusive. This is plain rhetoric, since the situation on the ground is abysmal, there’s a humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan. None of the expectations of the international community have been met i.e., creation of inclusive government; general amnesty for officials of the previous government; protection of women’s rights; and denial of Afghan territory to transnational terrorist groups.

Pakistan’s paradox is evident. In 1996, when Taliban 1.0 seized control of Kabul, Pakistan was quick to recognise the Taliban Government. As a matter of fact, it was one of the three countries that formally recognised that government. This time around, until as recently as December 2021, Foreign Minister Mahmood Qureshi stated that the time to recognise the Afghan Taliban government “has not come yet”. In fact, Imran Khan would like Pakistan to be ascribed as “victim of Afghanistan conflict”.

The Taliban government is opposed to the border fence, in line with Afghanistan’s historic stance. With a cabinet comprising 90% Pashtuns, 30 out of 33 Ministers, the Afghanistan Government cannot be supporting a physical barrier cutting through the middle of Pashtun and Baloch areas.

TTP is violently resisting Pakistan’s move. In July 2021, TTP leader Noor Wali Mehsud openly threatened to wage war against Pakistan security forces with the aim to “take control of the border regions and make them independent”. Hundreds of TTP fighters have been released from prisons in Afghanistan since the Taliban takeover. In the last quarter of 2021, in separate incidents along the border areas, TTP killed 19 Pakistani soldiers and injured dozens. The month-long ceasefire and talks between TTP and Pakistan government, brokered with the help of Afghan interim government, failed to deliver any results.

While the Taliban regime in Afghanistan is unambiguous in its opposition to the fence, Pakistan’s Foreign Minister and the Pakistan Army are playing down the border incidents as “minor irritants”, “localised issues”, “act of miscreants'' etc. On the other hand, there are elements within TTP that believe the narrative of dispute between Afghan-Taliban and Pakistan Army is fabricated – a smoke screen behind which they will take joint action against the TTP.

Much to Pakistan’s chagrin, Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan is rising in the new political order. Taliban 2.0 is certainly not as Pak-pliable as they envisioned. The ‘good Afghan Taliban’ is certainly not proving to be so good after all, and the ’bad Pak Taliban’ is getting worse. It remains to be seen if ISI’s latest attempt to sub-categorise TTP into ‘rogue TTP’ and ‘pro Pakistan TTP’ will work.

Pakistan’s Ayesha Siddiqa, author of the acclaimed ‘Military Inc. Inside Pakistan's Military Economy’, had said that the US failed in Afghanistan because it “trusted Pak Army while dealing with Taliban”. Is Pakistan now scoring a self-goal vis-a-vis Durand, by trusting the Pakistan Army in dealing with Taliban?

Also Read: Taliban’s blunt message to Pakistan—Durand line as border is history

(The author is former Deputy Chief of Army Staff and Kashmir Corps Commander, and Member, National Security Advisory Board. Views expressed are personal and exclusive to India Narrative)