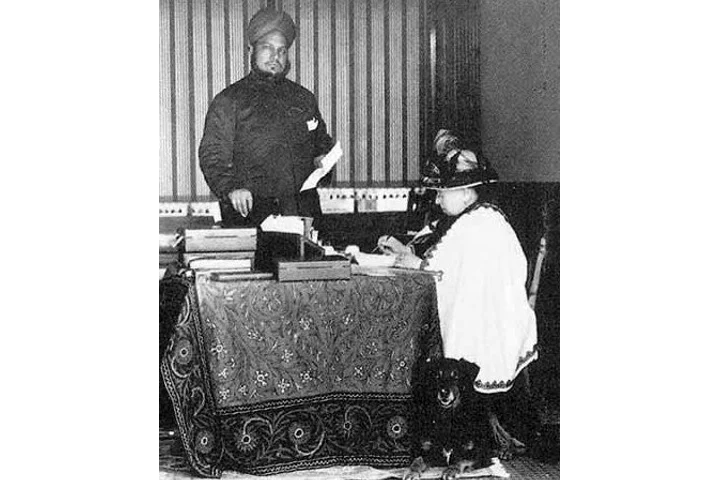

Abdul Karim and Queen Victoria—an unusual pair that brought the charms of Indian food to the British Empire (Photo: IndianHistoryPics/Twitter)

I was in London recently, curating a food pop up around India and UK ties in the run up to the coronation of King Charles this May. India and the UK have close and complex ties that go back not just to Independence, and almost 200 years of colonial presence before that (as you have read in earlier columns here) but to a century before that, when the British arrived as traders in India. While Indian food changed with the introduction of new ingredients via the British from south America—potatoes, cauliflower, carrots, sweet green peas, tomatoes and more were incorporated into Indian cuisines, ingredients not indigenous to the Subcontinent, it is a myth to think that the transaction was one sided.

Indian tastes and influences impacted British tastes too much like the fashion for paisley shawls from Kashmir in the early 19th century. We often find women characters wrapping these delicately around themselves in the works of authors like Jane Austen or even Georgette Heyer, but these were the weaves of India, and the paisley as it is called in the West, is nothing but the “amba” design of Indian art, inspired by the mango.

The Regency punch or the punch royale is a well known drink in Europe as well. It contains distilled alcohol, tea, some citrus and sugar/spices and all topped by a fizzy wine like Champagne. The original English punch however was a bit different and draws very clearly from an Indian drink called “paanch”, incorporating five ingredients. Paanch became punch as the early English traders adopted it and introduced it back home.

At the lunch function, Glenmorangie, the scotch makers with historic roots and one of the early companies to sell to all parts of the British empire, including the Indies after Queen Victoria, one of history’s famous scotch drinkers made it fashionable to consume this liquor, made a special Punch incorporating their original expression along with some delicious notes of citrus, masala chai and ginger – a homage to India and the drink’s Indian roots.

The first reference to Punch appears in a letter dated September 28 1632 by Roert Addams, stationed in India, working for the East India Company. He writes to a colleague about their accommodation saying, “I hope you will keep good house together and drincke punch by no allowance” (Punch by David Wondrich)”. The first recorded punch recipe actually goes back to 1638, when one Johan Albert de Mandelslo, a German managing the first English factory that was set up in Surat, records that the workers there made a drink made up of spirits, rose water, juice of citrons (lime) and sugar.

This is clearly an Indian recipe. The Indian Mughal aristocracy was fond of mixing wine with rose water, whose fashion was popularised by Noor Jahan. Arrack meanwhile was the distilled spirit of the common country people. The term used to refer to any distilled alcohol from fruit, flowers or grain—the art of distilling in royal regions of what we now call Rajasthan goes back centuries and the distilled spirits were spiced with cloves, roses, saffron and other expensive ingredients to make these a special occasion drink.

The early British in India who did not have access to these finer spirits, but rather to the arrack of the countryside may have started mixing it with rose water and lime in the prevalent Indian fashion to make the harsh alcohol tastier. We can only conjecture this. But as the fashion for punch spread in Britain, arrack was the spirit used (not rum from the Carribbean or European brandy, as later recipes started using), imported especially from India, Sri Lanka and Indonesia—all of which had Indian influenced traditions of distilling spirits since ancient times.

The Regent’s Punch, or George the fourth’s Punch Pare from the early 18th century is recorded as having the following recipe: the rinds of two china oranges, two lemons, one Seville orange, infused for an hour in half pint of thin cold syrup. Make a pint of strong green tea, and when it is cold, add the fruit and syrup, with a glass of best Jamaica rum and finally a glass of pink champagne. However, the punch that had been known in England for a century and a half before that had also incorporated spices like nutmeg from trading with India and east Asia and arrack as the original spirit to be used in many earlier recipes.

In fact, if you read the works of Georgette Heyer, known for her Regency romances, but whose detailing of 18th and 19th century Britain is astonishing in the accuracy of words, phrases used, historical details of buildings and people as also of foods people ate, you will know that while punch was a drink the British high class men often mixed, many sticklers for “the original” or “correct” way to make it would use arrack, not the later day rum.

A delightful chant that one of Heyer’s heroes uses while mixing the punch is: “One sour, two sweet; Four strong, And eight weak”—obviously referring to the proportion of ingredients, citrus, sugar, distilled spirit, tea, which would all be topped by a fizzy champagne, making it five ingredients—paanch or punch!

Many of these ingredients — as you can see were imported from the “colonies” and therefore quite expensive. Sugar, imported alcohol, tea from China and India and even spices like nutmeg used in old recipes all made this an expensive cocktail that only the rich in the UK could afford. In 1690s in London, records say, a three-quart bowl of punch cost half a week of living wage. Punch bowls started becoming accessories to show off. This idea of luxury food and drink had been imported from India. Ironically, as well to do Indians now spend on exclusive luxury experiences in the UK, contributing to its economic revival, the wheel has come full circle.

Also Read: How the British crown impacted Indian food in London and Calcutta

Prime Minister Narendra Modi interacted with members of the Indian diaspora here on Wednesday as…

The city of Hamburg in Germany is set to host the 11th edition of India…

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has confirmed that two Iranian centrifuge production facilities, TESA…

The human rights department of the Baloch National Movement (BNM), Paank, has strongly condemned the…

In a major boost to India's coastal defence capabilities, the Indian Navy on Wednesday commissioned…

Volker Turk, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, on June 17 expressed concern over…