On January 14, special envoys from Turkey and Armenia met in Moscow to discuss normalisation of diplomatic ties that were severed in 1993. The envoys agreed to continue the dialogue, while the two estranged neighbours agreed to start chartered flights between Istanbul and Yerevan.

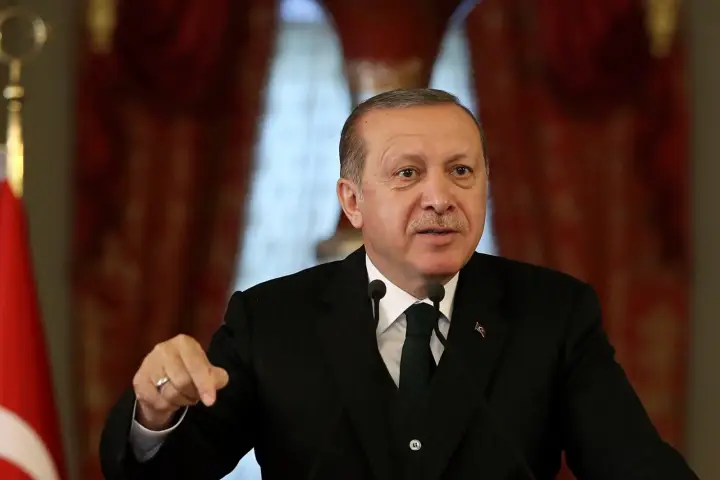

This engagement follows the high-level meeting in Ankara in November of the Turkish president and the Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi to patch up divisions that go back to the early days of the Arab Spring uprisings. In those upheavals across West Asia, Turkey had backed the Muslim Brotherhood, the principal political rival of the Gulf monarchies. Turkish president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, has also indicated a more conciliatory approach towards Egypt and the UAE in the conflict in Libya. Again, he has announced plans to visit the UAE and possibly Saudi Arabia in February.

These developments signal an extraordinary turnaround in Turkey’s militarised and aggressive posture in the region over the last few years. Does this portend a more moderate and cooperative Turkish approach towards its neighbours?

The Greek Parliament (Photo: Lefteris Partsalis/Xinhua/IANS)

Turkish foreign policy: three phases

Over the last two decades, during the rule of the Erdogan-led Justice and Development Party (AKP, in its Turkish acronym) from 2002, Turkey’s foreign policy has gone through three significant changes in content and approach. In the first few years, from 2002 to 2007, Turkey followed its traditional policy of prioritising relations with the European Union (EU), a period that is described by Turkish scholars as “the Golden Age of Europeanisation”.

This approach began to change under the influence of the distinguished scholar, foreign minister and later prime minister, Ahmet Davutoglu, who moved Turkey’s focus from the West to the East, towards the former territories of the Ottoman Empire in West Asia and the Caucasus. Davutoglu spoke of “strategic depth” and “zero-problems” as defining Turkey’s approach to its eastern neighbours. He emphasised that the principal diplomatic instrument that Turkey would use would be its “soft power” consisting of, as a Turkish scholar put it, “multilateralism, active globalisation [and] civilisational realism” that would make Turkey “a proactive, trustworthy, and great actor in the region”.

The approach is being referred to as “neo-Ottomanism” since it would be based on the religious and cultural ties that Turkey has with the former Ottoman territories. During this period, Turkey worked actively to address major regional conflicts – such as those between Israel and Syria or issues relating to Iran’s nuclear programme. Thus, through its peace efforts rather than military action, Turkey sought to obtain a central place in regional affairs.

This phase of Turkish foreign policy entered a new phase, signalled by Davutoglu’s resignation as prime minister in May 2016. Now, soft power gave way to the use of hard power in pursuit of national security interests – assertive diplomacy and military force being exercised on the basis of strategic autonomy, while retaining its “neo-Ottoman” character.

Domestic factors behind the new approach

In retrospect, this change appears to have been encouraged by important domestic developments that placed serious political and economic pressures on Erdogan’s government, beginning with the Taksim Gezi Park protests in Istanbul in May-August 2013. What started as a sit-in to protest an urban development plan finally encompassed over 70 cities and brought to the streets over three million people protesting against increasing authoritarianism and the perceived dilution of the secular order in the country.

However, it was the abortive coup attempt by a section of the Turkish armed forces in July 2016 that crucially transformed Erdogan’s domestic and foreign policies. He blamed the coup attempt on Fethullah Gulen, a reclusive religious figure who lived in the US and who had a large following in several parts of Turkish society. Erdogan also contended that the CIA was behind the coup and even issued arrest warrants for two former US intelligence operatives.

Again, he felt that the US and the EU, despite being NATO allies, extended only lukewarm backing to him during the crisis, as compared to Russian President Vladimir Putin who extended support telephonically ahead of Erdogan’s NATO colleagues and then invited the Turkish president to Moscow.

In response to these developments, Erdogan put in place at home an authoritarian, Islamist and security-centric order – factors that also shaped his regional foreign policy. In both domestic and foreign affairs, Erdogan obtained the backing from his coalition partner, the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP, in its Turkish acronym), that, as its name suggests, robustly supports his nationalist and militarist approach at home and abroad.

Besides seeking a central place for Turkey in regional and global affairs, these factors have also melded into one specific concern that animates the Turkish leader – the Kurds. After a period of mutual accommodation between the AKP and the Kurds during 2005-15, Erdogan, in response to some acts of domestic violence, began to adopt a harsh approach towards the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), that represents Kurdish aspirations for autonomy but which has been branded a terrorist organisation by Turkey and its allies.

This approach seeped into neighbouring Syria when the Syrian Kurds, taking advantage of the ongoing civil conflict, took control over large areas along the Turkey-Syria border to establish their ‘Rojava’, or western homeland. Since the Syrian Kurds are closely affiliated with the PKK, Turkey feared that the emerging Rojava would provide a sanctuary and training base for PKK militants.

Syrian soldier in the city of Manbij (Photo: Xinhua/IANS)

Turkish military forays in the region

In August 2016 Turkey sent its troops into northern Syria to occupy parts of the border territories and break the contiguity of the nascent Kurdish ‘homeland’. This offensive was followed by three more military incursions into Syria – in May 2018, in the northeast; in October 2019, in the northwest, and in early 2020 to establish control over Idlib province.

These actions have brought 8,835-square-kilometres of Syrian territory under Turkish control, which includes over 1000 settlements and towns such as Afrin, al-Bab, Jarablus, Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ayn. In this area, Turkey has set up a ‘Syrian Interim Government’ with several local councils that are controlled by a centralised Turkish military administration.

In the province of Idlib, Turkey has sought to combine its Islamist and anti-Kurd interests. From October 2017, its military presence in the province has been used not to attack the militants who are part of the Hayat Tahreer al-Sham (HTS), the former Al Qaeda-affiliated Jabhat Nusra, that dominates the region, but to protect them from Syrian government and Russian attacks. Turkey hopes that over time it will be able to persuade the HTS to join the militia it has sponsored – the Syrian National Army.

Beefed up by the HTS cadres, Turkey hopes to have a formidable military force made up of Syrian rebels under its command in northern Syria to curb any aspirations the Kurds might have to build their autonomous (or independent) homeland in the region. These extravagant Turkish plans have alienated both Russia and Iran – its partners in the Astana peace process.

In Iraq, Turkey’s military efforts are also linked with curbing Kurdish aspirations. Here, Turkey has successfully implemented a divide-and-rule approach – it has built close ties with the Iraqi Kurds represented by the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) that is influential in the Kurdistan Regional Government, and has used it against the PKK cadres that have taken refuge in the mountains in northern Iraq and regularly shell Turkish positions from across the border. In response, in addition to its major military base at Bashiqa, near Mosul, Turkey has several other bases in Iraq which it uses to strike at PKK militants as also prevent transborder cooperation between these militants and the Syrian Kurds.

Besides Syria and Iraq, Turkey has been recently involved in two other military initiatives – in Libya and the East Mediterranean and in the south Caucasus. In both theatres, Turkey has been motivated by the neo-Ottoman vision. In November 2019, Turkey entered into an agreement with the Islamist-influenced government in Tripoli to support it with militants from Syria. In return, it obtained a maritime agreement that created new Turkish claims in the East Mediterranean that encroach on the subsea energy claims of other littoral states, particularly Greece and Cyprus.

In Libya, in early 2020, the Syrian militants provided by Turkey were able to reverse the military successes of General Khalifa Haftar who represents the rival government authority in Tobruk. But this conflict has also placed Turkey in confrontation with Egypt, the UAE and Russia that are supporting the Tobruk authority.

In the South Caucasus, though not directly involved in the Azerbaijan-Armenia conflict late last year, Turkey was a principal role-player in the Azeri victory, which enabled the latter to win back most of the territory it had lost to Armenia in 1993 – this was largely on account of the drones that Turkey had provided Azerbaijan that were perhaps a decisive factor in determining the outcome.

Celebrating its military triumphs and signalling its centrality in regional affairs, in November last year, Turkey presided over the summit of the ‘Organisation of Turkic States’ that brings together Azerbaijan, Hungary and the Central Asian Republics (excluding Tajikistan). This organisation is pledged to promote cooperation in the areas of the economy, culture, education, transport, customs and the diaspora through institutions responsible for culture and heritage, a parliamentary assembly of Turkic states, and Turkic chamber of commerce.

Problem areas

Turkey’s single-minded and aggressive pursuit of its interests over the last few years has over-stretched its capabilities and alienated a number of important partners.

Turkey’s claims in the East Mediterranean have encouraged both the US and France to come to Greece’s assistance through fresh military agreements. France and Greece concluded a strategic partnership agreement under which the former will boost Greece’s armed capabilities with frigates and Rafale aircraft as well as a mutual assistance clause in case of attack, a direct reference to Turkey’s possible aggressiveness.

The US conveyed its support for Greece in October last year at their bilateral strategic dialogue when, in an obvious reference to the East Mediterranean disputes, the joint statement emphasised the importance “of respecting sovereignty, sovereign rights [and] international law, including the law of the sea”. The US also affirmed its commitment to developing Greece’s military infrastructure and increasing arms supplies.

More seriously, Turkey’s assertion of strategic autonomy, which has meant balancing its ties with the US and Russia, has caused concerns in the US – the latter has not accepted Turkey’s purchase of the S-400 missile system from Russia. It has evicted Turkey from the development of the F-35 fighter aircraft, a major NATO project, and has imposed sanctions under the ‘Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act’ (CAATSA).

President Biden has also reversed Trump’s accommodativeness towards Turkey, signalling the US’ new approach in April 2021 by formally recognising the Armenian genocide by the Ottomans in 1915, despite strong Turkish opposition over several years. The message from Washington is clear – Turkey will need to fulfil all its obligations if it wishes to remain a NATO member.

However, Turkey has also alienated Russia – many of Turkey’s regional initiatives have placed it in confrontation with its partner. They are on opposite sides not just in Libya and Syria (on account of Turkey’s camaraderie with the HTS), but also in the south Caucasus where Turkey stood against Russia’s ally, Armenia.

But the matter of immediate concern for Russia is the persistent Turkish backing for Ukraine in the ongoing standoff. Turkey had rejected Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, seeing the militarisation of the peninsula in the Black Sea as a security threat. Turkey has since then enthusiastically supported the NATO membership of both Georgia and Ukraine and has supplied its Bayratkar TB2 armed drones to the latter.

Amidst these tensions, Turkey has sought to mend fences with the US by seeking to purchase 40 new F-16 fighter aircraft and modernisation kits for 80 others. To appease Russia, it has offered to mediate on issues relating to the provinces in eastern Ukraine which are controlled by pro-Russian separatists.

Neither initiative has worked: in the US, Turkey’s request faces congressional opposition, while on Ukraine, Russia has firmly rejected the mediation offer by asking Turkey “to contribute to encouraging the Ukrainian authorities to abandon their belligerent plans” for the eastern provinces. Russian sources have also criticised Turkey for fanning “militarist sentiment” in Ukraine.

Even as both the US and Russia display little enthusiasm for Turkey’s brinkmanship, the limits of Turkey’s civilisational outreach in Central Asia were dramatically revealed when angry protests erupted in Kazakhstan on 2 January. Now, instead of seeking help from his Turkic ally, the Kazakh president, Kassym Tokayev sought Russia’s assistance under the Russian-sponsored Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO). Tokayev blamed foreign agents for the “coup attempt” – some Turkish observers believe this could have been aimed at Turkey which has been frequently criticised by Arab and Central Asian states for backing Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated Islamist groups.

People celebrate the first anniversary of the foiled coup attempt in Turkey in 2017 (Photo: Xinhua/IANS)

Factors encouraging Turkey’s foreign policy review

In the background of the challenges that have emerged in response to its hardline assertions in the region, Turkey has initiated positive overtures to its neighbours in West Asia with whom it has had the most contentious of ties for many years. Four reasons could explain this fresh approach.

First, perhaps, the most important factor is the region-wide conviction that the US now has very limited interest in West Asian disputes. This US disengagement from the regional scenario after a forty-year history of robust political and military interventions has provided regional states their first opportunity to engage with each other and explore the possibility of fresh relationships.

Second, linked with this is crisis-fatigue: from 1980 onwards, West Asia has witnessed near-continuous conflicts which have caused widespread death and destruction and imparted a deep and abiding sense of instability and insecurity across the region. More recently, West Asia is experiencing wars in Syria and Yemen and the challenge posed by the transnational entity, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). Though military efforts have ended the threat from ISIS, several of its cadres remain across the region and carry out sporadic, though lethal, acts of violence against vulnerable targets. The wars in Syria and Yemen, however, continue, and, despite the destruction and human misery, have not yielded a military result.

Third, these developments have been taking place amidst the COVID-19 pandemic that has devastated regional economies, disrupted manufacture, and deprived millions of their employment and livelihood. This challenge calls for a region wide effort to reduce divisions and conflicts and pool resources for shared benefit.

Finally, the one factor that has helped to prepare the ground for fresh engagements among contending nations in West Asia is that divisions created by the Arab Spring uprisings a decade ago have lost much of their resonance. In the early period of the uprisings, Gulf monarchies perceived a real challenge from popular wrath and believed that the Islamists, represented by the Brotherhood, posed a palpable threat to their thrones. They were particularly mortified by the success of the Brotherhood in Egypt and worked hard, with the Egyptian armed forces, to discredit the government and bring it down through a coup d’etat in July 2013.

This had sharpened the ideological divide between Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Egypt on one side and Turkey and Qatar on the other, and led to the blockade of Qatar by the kingdom and its allies in June 2017. This siege strengthened ties between Qatar and Turkey, when the latter moved swiftly to provide military, political and economic backing to its Gulf partner.

Much has changed since that fraught period. Saudi Arabia and its allies now believe they have successfully handled the challenge from the Arab Spring uprisings and do not see the Brotherhood – now in disarray ideologically and organisationally across the region – as posing a threat to their regimes. Reflecting this perception, Saudi Arabia led the other GCC countries in ending the Qatar blockade in January 2021, despite there being no change in the positions that Qatar holds, which had caused the blockade in the first place.

It is in this background that Turkey commenced last year the difficult process of mending ties with its Arab neighbours.

Towards a “zero-problems” foreign policy?

Since May last year, Turkey has reached out to Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Turkey and Egypt met at ministerial level in May and September and have agreed to maintain the tempo of interactions. To improve the atmosphere, Turkey has curbed the stridency of anti-Egypt broadcasts by Brotherhood exiles, while agreeing to back a new political process in Libya that would lead to a unity government in place of the divided political order in the country.

There has been some forward movement with Saudi Arabia as well. In May last year, Turkish foreign minister, Mevlut Cavusoglu, visited Riyadh and interacted with his counterpart, Prince Faisal bin Farhan; they agreed to “work on positive issues on the common agenda and hold regular consultations”. Later, on 25 November, the Saudi trade minister, Majid bin Abdullah Al-Qasabi, met the Turkish vice president, Fuat Oktay, in Ankara, signalling the shared interest of the two countries in improving ties, starting with the economic engagements.

Turkey’s interactions with the UAE have been even more robust. In August last year, the UAE’s national security adviser, Sheikh Tahnoun bin Zayed, visited Ankara; this was followed by a telephonic conversation between Erdogan and Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed, crown prince of Abu Dhabi and de facto ruler of the UAE. On 24 November, the crown prince visited Ankara, his first visit in eleven years. The visit led to prospects of significant UAE-Turkish economic ties, starting with a $10 billion UAE investment fund for the energy, infrastructure and health sectors.

Amidst this flurry of diplomatic activity, Turkey has not ignored its traditional ties with Qatar. Erdogan visited Doha on 6-7 December, an interaction that highlighted the close links between the two countries – they have each invested about $32 billion in the other country, even as Turkish contractors are executing projects worth $18 billion in Qatar, mainly for the 2022 World Cup. During the visit, Erdogan affirmed the shared interest of the two countries in “peace and well-being in the entire Gulf region” and added: “All of the Gulf peoples are our true brothers.”

However, the most significant interaction that Turkey has had recently has been with Armenia. The historic animosity between the two peoples that goes back to the Ottoman ‘genocide’ of the Armenians during the First World War obtained a fresh resonance when Turkey backed Azerbaijan in the conflict with Armenia in September-November 2020. Azerbaijan then succeeded in recapturing seven areas in the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh region, evoking fresh hostility towards Turkey in Armenia.

On 14 December, under EU auspices, the Azeri and Armenian leaders met in Brussels and agreed on the demarcation of borders and restoration of railway connections. On the same day, the Turkish foreign minister announced that his country would pursue normalisation of relations with Armenia, while coordinating each step with Azerbaijan. Both countries then appointed special envoys to take the normalisation process forward. These envoys had their first meeting in Moscow on 14 January, which they described as “positive and constructive”.

Outlook for the “zero-problems” approach

What we are witnessing now is a degree of back-paddling by Turkey after about four years of aggressive diplomacy, supported by military interventions, to obtain a central place in the regional scenario.

An objective assessment would suggest that Turkey spread its initiatives and assertions far too widely, thus placing considerable pressure on its resources. It also, in the process, generated a strong pushback from several quarters – Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Egypt – while alienating powerful partners as well, the US and Russia.

Again, problems of inflation, currency depreciation and youth unemployment have alienated large sections of the domestic population, encouraging talk of possible setbacks for Erdogan in national elections in 2023. Turkey thus had no option but to review its approach and pursue policies of re-engagement. Since foreign affairs is Erdogan’s personal domain, drastic policy reversals have been relatively easy to initiate. However, clearly, there is far too much ground to cover and far too many corrections required – many of which could be beyond the capacity, or interest, of Turkey’s modern-day sultan.

For instance, Erdogan will not be able to distance himself entirely from political Islam or the Brotherhood – political Islam is central to his party’s ideology, it is at the heart of “neo-Ottomanism”, and it defines Erdogan’s persona. Hence, it is unlikely that he will be able to obtain the full confidence and trust of his Arab rivals. The best that is likely to emerge is lowkey working relationships, but mutual distrust and rivalries based on their ideological divide will endure.

Erdogan’s brinkmanship vis-à-vis relations with the US and Russia has persisted well past its use-by date. It endured largely because of Trump’s accommodativeness and Putin’s interest in quietly working to detach Turkey from NATO. Today, the situation is quite different – Biden does not have the tolerance of his predecessor, nor does Putin have his earlier patience. Turkey’s overt military support for Ukraine and backing for its NATO membership just when Russia is confronting Western powers on an issue it sees as of crucial importance for its national security is likely to be seen as a serious betrayal.

Beyond the immediate matter of Ukraine, Russia will not take kindly to the Turkish president encroaching into its traditional domain in the south Caucasus and Central Asia, despite the blandishments of Turkic culture that Erdogan proffers. It is not clear with what success Erdogan will be able to assert strategy autonomy in this contentious scenario.

That leaves the issue of the Kurds. On this matter, Erdogan has not offered an olive branch either at home or in the region — the use of force will remain the principal instrument to confront Kurdish aspirations.

The conclusion is unavoidable – despite the hectic diplomatic activity across the region, Turkey’s “zero-problems” policies are all froth, with no substance.

Can Armenia-Turkey ties improve in the shadow of the Armenian genocide?

Turkey challenges Russia, pushes into Central Asia with Organisation of Turkic States

Why is Taliban spurning Turkey's embrace of Afghanistan?

(The author, a former diplomat, holds the Ram Sathe Chair for International Studies, Symbiosis International University, Pune.)