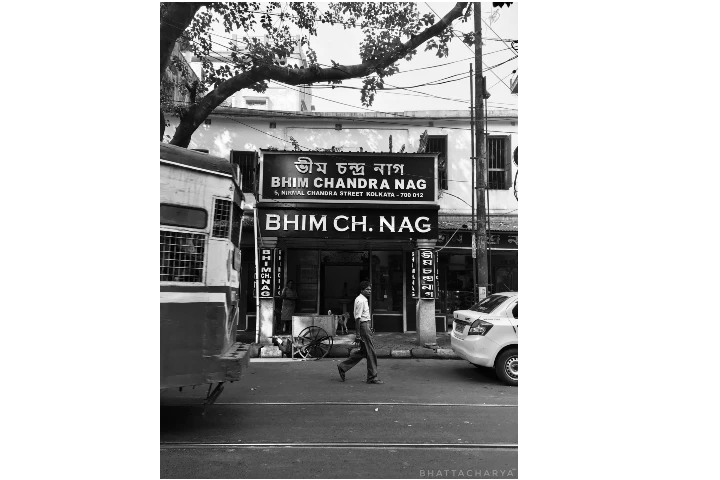

Bhim Chandra Nag—One of the 19th Century pioneers who introduced Sandesh in Kolkata (Photo: @BrandSouvik/Twitter)

Bhim Chandra Nag—One of the 19th century pioneers who introduced Sandesh in KolkataSandesh, the beloved Bengali mishti and one of India’s best-known sweets, means “news”, when translated from Hindi/Bengali, and the name carries with it the connotation of “good news” –an old Indian practice being “mooh meetha karana” (make the mouth sweet, literally) of any bearer of good tidings. That was in days when communication was much slower and sparser!

In this day and age, when communication and dispersal of cultures are instant via Insta, Sandesh is often described as “Indian cheese cake” to make it more relatable to western palates.

It is of course—made from chenna, a soft cheese obtained from splitting milk, cousin to the firmer paneer from which more moisture has been drained. But is this ancient Indian mithai any relation to the various styles of cheesecakes popular in Europe and America, from where they have now made their way into bakery shops and restaurant menus of a wider world via the globalisation of taste? Let’s compare the origins of the cheese cake and those of the Indian Sandesh.

Most people in India (and globally) would be acquainted with the New York cheesecake, made with Philadelphia cream cheese. It is a fairly easy to make dessert, with a crust of digestive biscuits, layered with thick cream cheese, and a third layer of sour cream on top balanced with something like the uber popular blueberry compote that started becoming a fixture in this cake after blueberry production in the US took off commercially in the 1960s (these were a native Indian American berry indigenous to that continent, and used for medicinal purposes, before North America’s colonisation).

This classic New York cheesecake, initially sold at Jewish bakeries at the turn of the 20th century, has become a favourite in Indian metros in the last 20 years. There is also a rather new fad of the burnt Basque Cheesecake in the last two years of the pandemic, as this version of the cheesecake made popular by San Sebastin restaurants and high-end Spanish gastronomy found global prestige.

Last year, the burnt (referring to the browned top of the cake, full of rich and complex notes brought about by a chemical process called the Maillard reaction, the phenomenon that makes charred foods delicious by concentrating flavours) basque cheesecake was dubbed the “it” dish in New York after the New York Times ran a list calling it one of the top new dishes to look out for.

That set off an Instagram trend, including in India, and restaurants and bakers started replicating the recipe. In Delhi, chef Dhruv Oberoi of Olive does what is possibly the best in India, should you want to try it.

If the Basque cheesecake dates back at best 20-30 years, the New York classic has enjoyed popularity since the end of the 19th century. In 1872, William A Lawrence, a dairyman in New York, stumbled upon a recipe for unripened fresh cheese while trying to make a French style soft cheese called Neufchatel. He called this simply “cream cheese” after its texture, and started producing it in bulk by 1873.

As its popularity soared, Kraft Heinz Co, commercial cheese makers, dubbed it “Philadelphia cream cheese” in marketing campaigns of the 1880s, to associate it with high quality dairy from Philadelphia. The creaminess of cream cheese sparked off the huge popularity of two dishes that we now associate with New York, particularly from its Jewish subculture– the bagel, and the cheesecake.

The cheesecake, however, was originally a European dish. English recipes going back to medieval times used various curds in tarts, and this has led to British chef Heston Blumenthal, pioneer of “multisensory dining”, claiming the cheesecake to be a British invention, though in the rest of western Europe too fresh cheese like the Italian ricotta (similar to paneer) have been traditionally used with flour and eggs to make curd or cheese cakes. Greek cakes that use yoghurt and fresh cheese are in fact still part of the Mediterranean food culture. Some accounts claim that an early version of the cheesecake was fed to athletes at the first recorded Olympic games in 776 BC in the city state of Ellis!

Medieval English or European recipes that featured the idea of cheese or curd tarts, with a thin base, and a topping made from coagulated milk to which rennet had been added, became common in America from the 18th century onwards, but with the invention of creamier, thicker cream cheese, the dish became a modern star.

In India, curd, and curd- based desserts like the ancestor of the shrikhand, shikharini in Sanskrit (dewatered curd with saffron and cardamom, beaten smooth), is mentioned in Sanskrit literature of 400 BC, according to KT Achaya. But there was an injunction in the Vedic culture against splitting milk, regarded as a ritualistically pure and nourishing food. So, India unlike Europe, the Mediterranean, Central Asia and others did not have a mainstream cheese making food culture (exceptions being tribes of the mountainous regions bordering central Asia and Ladakh).

Milk was instead preserved as khoya– milk solids obtained after slowly boiling down the water content, which every Indian will instantly recognise even today as the predominant base for the subcontinent’s unique mithai tradition.

There were various kinds of khoya, and still are, depending on how much of the water has evaporated after cooking the milk in an iron karahi. The early Sanskrit term for this milk solid was Shakarpaka, and this could be combined with sugar to give early versions of peda, barfi and laddoo (modak, associated with the god Ganesh, now a steamed rice dumpling in the Konkan regions, were initially khoa based laddoo, Achaya maintains).

Khoya was also the material for Sandesh, mentioned in early Bengali literature such as Chandimangala and Chandidasa of the 16th century, making the Sandesh in essence a sort of barfi, shaped differently and combined (as all barfis are) with regional ingredients and sugars.

Other mithai was made from different forms of thickened milk, including solidified kheer, Rabri lashings or dewatered curd. In fact, even today, the bhog in Vrindavan, has thick layers of malai that have been scraped off while the milk is cooking, offered as part of the chappan bhog. A group of chefs that I led to experience this food in the temple town likened it to ricotta, the European fresh cheese—and were excited at how this could be used in modern Indian gastronomy. But, of course, this was just thickened milk — and not European style cheese made from coagulation of milk with an acid (like lime juice).

Cheese-making, in fact, arrived in India’s mithai and vegetarian food tradition via Bengal, only after the Portuguese became the first Europeans to arrive in that part of the country as traders and established settlements in Satgaon and Bandel as well as control over Chittagong in the 16th century. They brought with them the European idea of splitting milk to make cheese and gave three types of cheese to Bengal—chenna, ponir (paneer), and the aged Bandel cheese that has now been discovered by trendy restaurants and chefs.

Paneer or panir, a general term for cheese in Persian, had been known in central Asia for centuries and came to parts of north-western India, via the Persian influence on Mughal food with some recipes from Shah Jahan’s time onwards incorporating it into the imperial food. In fact, the Venetian traveller Manucci records an insult by the Shah of Iran, Shah Abbas, to Aurangzeb, who had crowned himself emperor after deposing his father and killing his brother. When the Mughal ambassador in the Persian court showed a newly-minted coin by Aurangzeb, the Shah compared it to a worthless piece of panir!

Paneer did not make its way into the cuisines of most ordinary Indians till much later—after Partition, when immigrants from Punjab brought it to Delhi. Before paneer matar became a north Indian vegetarian delight, old Delhi (and my own Kayasth community, about whose cultural and culinary history I have written extensively) had the winter classic khoya matar, a disappearing dish today.

In Bengal, chenna slowly found its way into the handiwork of halwais. But most of the innovation with this new product seems to have only come about in the 19th century— ironically at the same time when the New York style cheesecake was being formed– under the patronage of the landed gentry, the Zamindars, who had built large marbled mansions in Calcutta. They had grown closer to the English elite of the day, adopting many of the foods and lifestyle of the ruling set, while still maintaining older religious identities and rituals.

While the Sandesh occurs in the songs of Chaitanya, the bhakti movement spiritualist as well earlier, it was likely made with milk solids and not cheese that was not regarded as a ritualistically pure ingredient by Vaishnavs, including followers in the landed gentry. But in the 19th century as social mores relaxed, more influences got absorbed into Calcutta’s fabric, mithai makers started experimenting with this new material to come up with lighter sweets.

Sandesh made with chenna was made popular by confectioners like Bhola Moira, Bhim Nag (1809-1885) and Girish Chandra Dey. Many different kinds of Sandesh were invented, using not just the notun or new palm jaggery of the season, but also rose water, mango and shaped in various ways.

The famous and elusive jalbhara sandesh, filled with “water”, as the name suggests, was possibly made as a paheli ka khana, then popular in aristocratic food traditions of Lucknow, Hyderabad and Bengal, where during a wedding feast, the groom is fooled by a deceptive delicacy to much merriment. The story goes that a rich landowner commissioned this as a speciality during his daughter’s wedding and when the groom bit into it, the rose water filled inside, spilled on to his kurta.

I have read some blogs written by Bengalis that also argue that this Sandesh (that may have been the predecessor of the modern-day delicacy filled with liquid notun gur) may even have been inspired by European liqueur filled chocolates. But these are conjectures.

Today, as Indian chefs go about tweaking the Sandesh even more, trying to incorporate it into a western patisserie or desserts tradition, and dub it the Indian cheesecake, it is an unwitting nod to how a humble food of Mediterranean shepherds from ancient times spread globally and was assimilated into popular dessert traditions of both the east and the west. Food cannot have political boundaries.

Also Read: The monsoon magic of Chai Pakoda—did the British East India Company trigger the fusion?

From Amritsar to Georgia—the humble Kulcha’s extraordinary journey to Caucasia

Chinese officials have interrogated and detained local Tibetans who shared photographs and posts on social…

Paank, the human rights division of the Baloch National Movement (BNM), has said that there…

The Indian Army showcases its prowess in the Plateau Sub Sector along the Line of…

The Indian Army has successfully concluded ARMEX-24, a high-altitude adventure expedition that stands as a…

The US Department of State, during its press briefing, addressed the questions on the rise…

The team of Indian Army's Field Hospital deployed in Mandalay under Operation Brahma returned to…