One of the most common mistakes people, particularly foreigners not particularly acquainted with the diversity of Indian cuisines, make is to mistake spicy for chilli, and stereotype all Indian food as “spicy” when what they possibly mean to say is that they find it hot (which is also not true, since a huge number of dishes are mildly spiced).

Yes, Indian gastronomy is based on the use of spices, in different combinations and in complex ways which may seem bewildering to people not from the Subcontinent—and who may only be able to taste pungency instead of a layering of different notes of flavours and aromas. But Indian food is not based on chillies, even though we use them commonly in our kitchens.

In fact, chillies as just one of the many spices in Indian kitchens, were not even used in Indian dishes till well into the 18th century and even later.

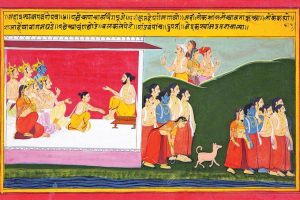

If you look at medieval recipes, whether they be from the 16th century recipe tome Nimatnama, put together by kings of the Malwa Sultanate, or the Nuskah-e-Shahjahani, whose handwritten manuscript with recipes from the early Mughal period is kept in the British Library, you will find black pepper used in royal recipes to impart some heat or pungency to the food and thus balance flavours.

In fact, a mix of ground cardamom and black pepper was used to scent and flavour the dishes at a finishing stage, after the main cooking was complete, and a reading of these recipes makes it clear that the food was certainly not as “hot” as many gravies of Indian dishes may seem today, especially when inexpertly cooked by restaurants.

Spices were used in different stages of cooking to layer aromas, and provide complex tastes, but more importantly for their therapeutic value, according to Ayurveda or the unani system of medicine, influenced by early Indian knowledge that mingled with Greek thought in the Arab world in the pre-medieval trading ports such as Alexandria.

Indian royal kitchens, particularly those of the Mughals and subsequent subsidiary rulers such as the nawabs of Avadh and Bengal and the Nizam of Hyderabad, had physicians advising chefs on the use of specific spices in dishes to promote health and vigour. In Lucknow, the early 20th century book Guzishta Lucknow talks in detail about how hakims advised on intricate formulations: these used not just elusive and rare spices such as stone flower (pathar ka phool, or lichens), but also ingredients like dried rose petals, dried seeds of melons, silver and gold dust as well as extract of pearls, and even a distilled essence of the earth or soil .All these were used in food to create sensory delight but more importantly because of their medicinal properties or taseer/guna as ascribed to them, whether they could cool the body or heat it etc in the medieval systems.

Abdul Halim Sharar عبدالحلیم شرر(1860-1926)was the foremost Urdu writer & cultural historian from Lucknow. He had 102 books in his name.His book Guzishta Lucknow is the most authentic account of the Lucknow of late 18/19th centuries that dwindled slowly in the early 20h century pic.twitter.com/eVH1Fymyql

— Khalid B.Umar (@khalidkoraivi) December 5, 2019

But while gastronomy became more complex with these ingredient mixes, at its simplest, the idea of seasonality was firmly embedded in Indian cooking and use of spices. According to Ayurvedic knowledge widely followed then, the body needed to adjust to changing weather to keep the balance of humours or the three doshas, and this was done through food.

So, winter months brought about an increased use of “warming spices”— like pepper and cloves and badi elaichi, as well as nutmeg, mace etc. This was the origin of “garam masala”, the spice mix that bewilders most foreign palates and is now regular in Indian kitchens. Garam masala was initially home made and used only in specific dishes in the winter. Its summer counterpart was the “thanda masala”, a mix of cooling spices such as mustard and poppy seeds, still used to cook fish in Bihar and eastern UP.

Since these spices and their complex blends had the power to dominate the palate with aroma and taste, through the years, they began to be used by commercial cooks and sometimes home cooks as something to be sprinkled on top of a finished vegetarian or meat dish not just to add another layer of flavour, but to hide any faults in cooking. Thus, an excessive use of spices in Indian food was an aberration and even now, a great dish is judged not by its spicing but judicious spicing.

Vegetarian dishes which are lightly spiced thus are the best way to determine a cook’s competence, those of us who regularly critique restaurants know this and use this while making our judgement calls. Drowning out every other flavour with a use of chillies is not the hallmark of competent Indian cooking—rather inexpertly cooked food relies on these hacks.

While chillies are thought to be the mainstay of Indian cooking, this is clearly a misconception and stereotype—it is some of the “warming spices” that provide heat and a sense of pungency and have a complex flavour profile.

While black pepper was used by the rich—it was also one of the most expensive commodities to have been exported from India to Europe through antiquity– local berries and fruit were also used as substitutes to pepper in local regional foods of the common people to impart an element of sharpness or pungency in dishes. In north India, pipli, or a long pepper, was used and it can still be found growing wild in the green areas of Delhi.

Chillies arrived in India with the Portuguese in Goa. Europeans, reliant on Indian black pepper to preserve and flavour meats, had been on the lookout for direct access to spices. Till the 16th century, the spice trade between the east and the west was controlled by Arab merchants and the price of these commodities was very high in Europe. While Columbus famously discovered South America in 1492, just a few years later, Vasco da Ggama, landed in Calicut, pepper country, in 1498.

Chillies, native to central and south America—countries such as Peru—were taken by Europeans as a pepper substitute to not just Europe but introduced to southern India too. But their cultivation and use remain limited till much later—in fact till three more centuries had passed.

Chilli peppers belong to the nightshade family, Solanaceae, which is the same as tomatoes, potatoes and aubergines.

They originated in Central and South America, and there’s evidence that they were first cultivated as a crop around 3000BC – making it an ancient plant! pic.twitter.com/ngstzyeAeG

— Kew Gardens (@kewgardens) July 1, 2021

The easy and cheap pungency chillies bought to the palate was harnessed initially to produce achars or condiments to accompany the food that grew popular in Mughal times and borrowed from the more ancient chutney and preserves/pickles tradition of India, where fresh ingredients were mashed up into a side dish to make for sour/pungent or sweet/sour notes, or preserved in salt and oil to make pickles.

According to the Hobson-Jobson: The Definitive Glossary of British India, the word achar first finds a mention in 1563 in the works of Gracia da Orta, a Portuguese physician. The word achar it may be conjectured comes from the Spanish aji, or chilli paste. But it is interesting to see how the Ayurvedic/Unani idea of pepper being used medicinally seemed to have been followed by European physicians too, who now experimented with the therapeutic effects of the new pepper, or chilli.

#1: Hobson-Jobson: The Definitive Glossary of British India Hobson-Jobson: The Definitiv… http://t.co/emgYwDDxHk pic.twitter.com/a99TZMn8e9

— Kindle Store (@kindlepurchase) February 15, 2014

While chillies were grown in Goa and some parts of southern India, in northern India, the dominant taste was for sweet, and sour dishes, mildly spiced, as we can see from Mughal recipes. With the decline of the Mughal empire and the Marathas taking charge of Delhi, many central and south Indian tastes and flavours seeped into the culinary fabric of northern India, including it is conjectured, chillies.

Today, Indian food is incomplete without a dash of chillies. But it is also important to note, that the best Indian food uses the heat in a controlled way, and is far more complex with a layering of different spice notes than just chilli.

Also Read: How colonial Britain bungled in viewing diverse Indian cuisine as a mere ‘curry’