By Rahul Halder

Life in military cantonments for children at a growing age can be either dreary or interesting depending on the nature of activities at the military base. Irrespective of the location of the cantonment, which could be in the remotest of places, the unique blend of culture and tradition, the range of sports and physical activities and the general atmosphere of bonhomie that prevails in a cantonment surpasses the best of community life that one can perceive anywhere.

My father was posted at one such Air Force station in Kolkata during the 1971 war, which saw intense air activity focusing on Bangladesh (then East Pakistan). As a nine-year-old then, those in this age group found our eco-system undergoing drastic change, with regular life hindered by black outs and sirens, apart from occasional bursts of intense air activity. One fine day, we found the serene forests surrounding the officer’s quarters where we lived being occupied by large anti-aircraft guns of the Army. The adventurous among us began spending time with the jawans manning the guns, savouring their delicious langar food.

Over a period of time, as the hostility intensified, the dangerous and ugly side of the war became increasingly stark. The station was abuzz with news of dead bodies of soldiers being flown in from East Pakistan, besides an unending flow of injured soldiers who were quickly moved to the military hospital. The essence of life -and-death dawned on me while interacting with the fighter pilots who camped in tents along the runway before heading for sorties at short notice.

Families of officers were encouraged to meet them once in a while to cheer them up. While one got to know a few of them well, it was a horrifying experience to see some of them not return from their sorties. The tents bore a forlorn look leaving an air of emptiness in their sudden absence, which took a long time to sink in.

When the war just got over and Bangladesh was yet to be established as a nation, few adventurous families from the station decided to visit East Pakistan to witness the ravages of a war-torn country. Not a bright idea though, but it was driven by the thought of being part of the celebrations by the Indian Army at ground-zero of their victory.

We thus visited Jessore and Khulna – the two prominent towns of Bangladesh, by road in a couple of Ambassador cars from Kolkata. Roads on the other side of the border were far better and beautifully dotted with trees, except that one would abruptly come across large gaping holes in the middle of the road created from shelling by Pak army tanks. As we moved deeper, one could see village-after villages deserted and houses burnt.

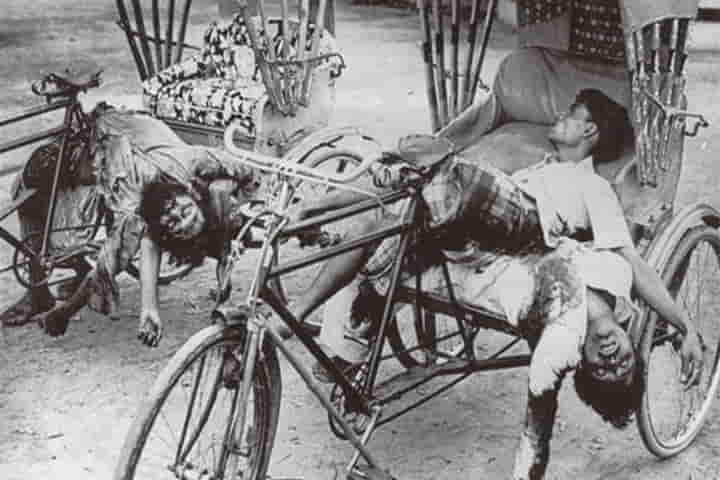

Refugees stream across the River Ganges Delta at Kushtia, fleeing the violence in East Pakistan during the West Pakistani military campaign called Operation Searchlight

The ruthlessness with which the Pakistani Army had ensured death and destruction, taking vicarious pleasure in killing Hindus and Bengali Muslims who were averse to the Pakistani Army, was starkly visible. The water in most of the nallahs that ran along the road was muddy red from the blood of hundreds slaughtered and dumped in these tiny rivulets and ponds by the Army. Since the war had just got over, one came across truckloads of victorious Indian troops weary and fatigued, returning from the fighting zone with the sign of eternal pride written over their faces.

Meanwhile, the Mukti Bahini (`Liberation soldiers’ as they were known) of Bangladesh was still around with young members of the bahini of 16 – 17 yrs. of age carrying Sten guns showing off their onerous contribution to the war. They would take pride in taking us to locations where bodies of Razakars, who assisted the Pakistani army in fulfilling their missions and later killed by the Bahini, lay bare for the public to see. In most cases, the severity of the revenge by the Mukti Bahini was evident with eyes of the dead Razakars gouged, and limbs amputated. The Mukti Bahini claimed that this was a reaction to the sordid experience each soldier had with their families butchered by the Pakistani Army while they went underground fighting the liberation war.

The supposedly high point of the visit, which turned out to be a sad and grim experience, was the visit to the village of Chuknagar in Khulna district. The Mukti Bahini insisted that any visitor to the newly liberated land should witness the tragic and gruesome acts of genocide committed by the Pakistani Army at this small village. As we entered the village square, a pall of gloom hung in the air which was interspersed by an eerie smell of death and destruction. On being asked, we were told that almost the entire population of the village and a large number of Hindus who had escaped the Pakistan Army from different locations across East Pakistan and had gathered at this village on the way to the Indian border were all slaughtered. The incident took place seven months ago on May 20, 1971.

The Mukti Bahini showed us an open field where the Pakistani Army contingent first arrived and opened fire at those on their way to India. After wiping out most of them, as some jumped into the nearby river and drowned, the troops moved on to the main bazaar area and the houses, opening fire at any one they came across. The Mukti Bahini showed us patches of dried trickle of blood which had turned black flowing from the village to the river following the killings. Despite months gone by since the incident, there were still telltale marks of the gory massacre that took place here.

Walking through the village, one found a number of very old and frail men and women huddled in different places. We were told that the Pakistan Army Major commanding the unit that carried out the massacre, apparently took mercy towards old residents of the village and let them go. It was painful conversing with them and hearing their sordid saga. Most of them were wailing away, reasoning the purpose of their existence without their children and grandchildren.

Some aged villagers had even committed suicide since the massacre, unable to bear the pain and loss. Few of them mentioned that they ran after the jeep of the Major requesting him to finish them off, but he restrained his soldiers from firing at them.

The village square had a number of trees which appeared painted red along the trunk till the Mukti Bahini mentioned that villagers were tied to these trees and shot at. Some of the houses we tried to peep in had the hallmark of a genocide factory with dry blood splattered on the walls and bullet marks all across. The Mukti Bahini had intentionally retained these houses in their original form to showcase the intensity of violence the Pakistani Army had indulged in. The goriness of the situation was beyond my ability to absorb and I was stung by the realization that such a colossal proportion of mayhem can be caused by one human against the other.

Though the massacre in Chuknagar was one of several such massacres that took place in different parts of Bangladesh, a post war assessment of all such incidents during the 1971 war indicated that the Chuknagar massacre was the worst of them all with around 10,000 people killed over a period of five hours of consistent firing by the Pakistani Army. The troops entered the village at 10 am and indulged in intense firing using Light Machine Guns and semi automatic weapons before departing at 5 pm. We donated funds, clothes and medicines to the villagers and tied up with the Mukti Bahini for Indian Army assistance to be extended to the villagers in whatever way possible.

Chuknagar was just a glimpse of the nature of killings that took place across Bangladesh with around 3 million people being exterminated and around 200,000 women raped. The Pakistan Army had launched operation `Searchlight’ on March 25, 1971 with the aim of crushing `Bengali resistance’ by targeting members of the Bengali community including military and government officials, intellectuals, students and all able-bodied Bengalis who could possibly pose a threat to them.

For me personally, being in this war-ravaged land had a special relevance as my parents originally hail from East Pakistan, and we had grown up hearing stories of the finer side of life in that part of Bengal with the green pastures and unending lakes, ponds and rivers that dotted the land. Besides, the intellectual richness that existed among the Hindus there was considered rare and unique.

While most members of families from both my parents’ side had moved to India during or soon after the partition, one of my maternal uncles continued to live in East Pakistan throughout and was a district official in Manikganj, close to Dhaka when the Pakistan Army began hunting for Bengali Hindus. We had no news of him and his family of three children aged 6, 9 and 12 besides my 70 yr. old grandmother who lived with him. We had kept a watch at the border point in Bongaon in West Bengal where most refugees from Bangladesh arrived since we had sketchy reports of their having left their house in darkness to avoid confronting the Pakistan Army.

One fine day, we got the news of their arrival at Bongaon, bruised and battered as they moved through farm lands and forests during the night and stayed with friendly Muslim families offering them shelter during the day. It took them 19 days to cover the approximately 170 Km distance to the Indian border. The grandmother, being unable to walk, was tied in a baggy hold and carried behind my uncles back all throughout. It was a great relief to see them all alive at the end of the painful ordeal of escaping the Pakistan Army.

As the war ended, Sheikh Mujib-ur-Rehman who was held in prison in Pakistan was released unconditionally and travelled to London and Delhi before arriving in Dhaka on January 10, 1972 to a cheering crowd preparing the onset of a new nation. Subsequently, on February 6, Sheikh Mujib undertook his first foreign tour as Head of the government to Kolkata to address the people of Bangladesh and India. Kolkata was undoubtedly the central node of all operations in Bangladesh.

The Indian Air force was smart in ensuring that Bangabandhu Mujib, as Sheikh Mujib was fondly referred to, was flown in a chopper from place to place in and around Kolkata accompanied by an Indian Air Force officer who belonged to district of Gopalganj in Faridpur (then East Pakistan). Was it a tryst with destiny or mere coincidence, my father hailed from the same place as Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib and arrived in India in 1949 for better education and opportunities. He later joined the Air Force and was involved in the operations in Bangladesh. The thrill in the eyes of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib, being accompanied and escorted by someone from his own town dawning the uniform of the IAF that had liberated Bangladesh was beyond belief. He hugged my father and held him for long thanking him for his special contribution to creation of Bangladesh, being from the same land.

As the dynamics of the region changes year after year with Bangladesh emerging as a successful nation with a vibrant economy brazenly facing all challenges that confront the nation, my thoughts always go back to the insurmountable human disaster that Bangladesh faced at the hands of the Pakistani Army and how the larger world community has remained aloof from this reality. During my travels across Europe and visits to some Nazi concentration camps there, I realized the severity of the mass killings and the element of brutality that occurred in Bangladesh over a short period of time far surpasses the intensity of the holocaust during the Nazi era.

I can only conclude by remembering the few impacting words of Sheikh Mujib’s historic speech at the Brigade ground in Kolkata when he repeatedly spoke of the “unity of feelings between the peoples of Bangladesh and India in their ideals and beliefs”. He hoped that “Bangladesh would prosper amid undying friendship between the two countries”. With the country in the hands of his daughter Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, who has grown seeing politics from the time of the country’s creation, we can be rest assured that the spirit of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib binding the two countries together will remain eternal.

(Rahul Halder is a freelance writer who visited Bangladesh as a child at the end of the 1971 liberation war, Views expressed are personal)

Also Read: Bangladesh pays tributes to Rabindranath Tagore on his death anniversary with songs and poems