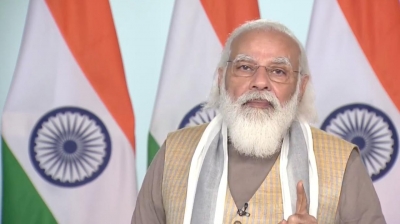

The Narendra Modi government’s decision to open up defence production to enhance self-reliance also has the potential of boosting Make in India. And, if implemented properly, this will go a long way improving military preparedness.

Make in India for self-reliance in defence production will be promoted by notifying a list of weapons and platforms for ban on import with year-wise timelines, indigenization of imported spares, and separate budget provisioning for domestic capital procurement, a government press release said. “This will help reduce huge defence import bill.” Indigenization began long ago; it got galvanized by a Missile Study Team, headed by A.P.J. Abdul Kalam of the Defence R&D Laboratory.

The Integrated Guided Missile Development Programme, which began in 1983, suffered due to the denial of technology. But this also promoted indigenization, which gained momentum in the 1990s. Defence production got a fillip in March 2001 when the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government decided to open up it to the domestic industry and allow 26 per cent foreign direct investment (FDI). As usual, the decision was opposed by the Left; for some strange reason.

Parliamentary affairs minister Pramod Mahajan, while announcing the decision, said that the earlier policy was anomalous in the liberalized scenario. At any rate, he argued, it was incongruous and weird that the government could rely on the private sector of, say, Sweden and the United States but not its own domestic companies. To formulate the policy on defence production, the government immediately set up a committee. It was only in January 2002 that the committee submitted its report (The recommendations of the report did little to attract investment in defence production, but that is another story).

Two years later, however, the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance came to power—and all progress in defence production came to a standstill. For eight years in the UPA’s two tenures, A.K. Antony was defence minister. Defence preparedness suffered enormously under him; defence production hit one roadblock after the other. At the time he quit, the Indian military needed arms and ammunitions worth $100 billion. The well-known defence expert, Rear Admiral (Retired) K. Raja Menon, called Antony the “worst defence minister ever.” The Admiral was excessively harsh on Anthony, for the V.K. Krishna Menon, Jawaharlal Nehru’s favorite, the worst; Menon was actually a traitor.

But that’s another story. The UPA regime came up with the Defence Offset Policy whose purpose was to promote the domestic industry. A 2012 government directive said that the policy was intended “to leverage capital acquisitions to develop Indian defence industry by (i) fostering development of internationally competitive enterprises, (ii) augmenting capacity for Research, Design and Development related to defence products and services and (iii) encouraging development of synergistic sectors like civil aerospace, and internal security.”

The policy did little good to the country as procurements were minimal. Antony’s biggest problem, as also of the entire UPA’s, was his marked tilt towards socialism. So, the eight defence PSUs, 39 ordnance factories, three defence shipyards, and 52 DRDO laboratories continued functioning in typically sarkari manner. The private sector was anyway looked with suspicion.

The upshot was that our dependence on defence imports rose to around 65 per cent. Everything, however, came to a standstill during the 10 years of UPA rule (2004-14), with Antony presiding over a crumbling military-industrial complex. The liberalizing measures for defence production are part of the Rs 10-lakh crore economic package that the government has announced to fight the coronavirus.

“There will be time-bound defence procurement process and faster decision making will be ushered in by setting up of a project management unit (PMU) to support contract management, realistic setting of General Staff Qualitative Requirements (GSQRs) of weapons/platforms, and overhauling trial and testing procedures,” the official release said.