The Indian National Army trials was a historic event that took place between November 1945 and May 1946 at Delhi’s Red Fort. The trial was a court martial of a number of INA officers on the charges of torture, treason, murder and abetment to murder during the World War II, with all Indians cutting across their differences supporting the freedom fighters.

Virtually refreshing the memory of today’s generation about this event was the play “Lal Quile Ka Aakhri Muqadma” staged by Pierrot’s Troupe and directed by M. Sayeed Alam at New Delhi’s LTG Auditorium recently.

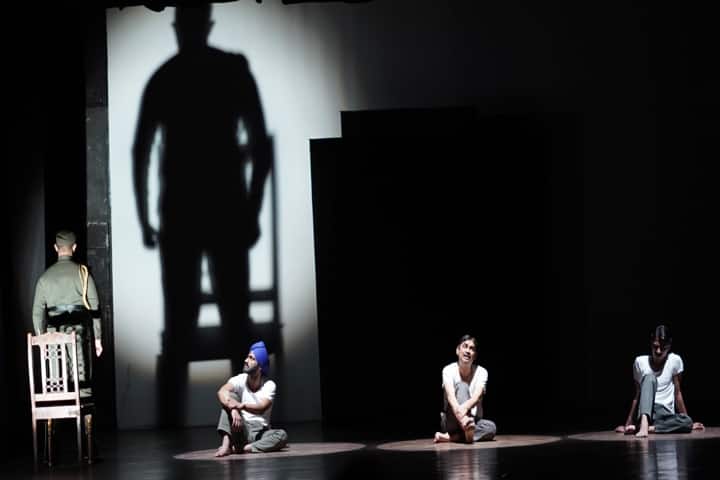

Sticking to a simple narrative format, the audience see three INA officers – Major General Shahnawaz Khan (Sayeed Alam), Col. G.S. Dhillon (Rohit Soni) and Lt. Col. P.K. Sahgal (Yash Malhotra) sitting in their cell, recollecting their struggle against the British; association with Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose who led them; trials and tribulations while discussing the court martial.

The play is engaging as it uses a past event to zoom on contemporary issues that are relevant. Agreeing with this, Mrinal Mathur, the playwright who also essayed the role of Bhulabhai Desai, who successfully and forcefully defended the accused, told Indian Narrative: “It (the play) touches upon the challenges of divisiveness, class, hypocrisy, racism, polarisation, bigotry and society’s social media fueled inability to see nuance and balance in people’s views and actions.” The trials, he said, provides “an interesting device to convey how a generation of people rose above similar challenges at a critical juncture in our history as a nation.”

Further, the play busts the prevalent myth that people with opposing views cannot respect each other and learn from one another. “This is why the play indicates that both Netaji and Gandhi ji, despite their much-advertised differences, were similar because they were fundamentally warriors of truth.”

To move the narrative back and forth seamlessly, Alam has Bose (Ritu Katare) dressed in olive green uniform donning Netaji’s famous cap, sitting on a chair on the left representing the past while Bhulabhai Desai is stationed on the right symbolizing the ongoing trial.

Interestingly, Netaji’s back is visible to viewers and not his face. Explaining this to India Narrative, Alam said: “I, with the permission of the playwright, decided about it the very first day I went through the script: It was the best compromise between Netaji not being the part of the trial and, he, at the same time, being the ‘raison d’etre of the trial.”

This placement is significant as the audience gets to see Netaji’s shadow falling on stage background, enhancing his personality and presence. “We thought that his ‘larger than life’ portrayal would cater to his perception in the eyes of the modern day audiences,” Alam remarked.

The performance of the five actors on stage was praiseworthy. While Dhillon and Sahgal brought up serious issues to the fore, Shah Nawaz’s character introduced a lightness to the proceedings through his witty one-liners and remarks. Taking a dig at the fascination of parents in India to get a fair-complexioned bride for their sons, he says though we fought the angrez, we still need a Dulhan who is gori. Likewise, quipping on the saying that everything is fair in love and war, Nawaz comments that while fighting one must adhere to rules and that fondness for a person should never get transformed into a battle.

These dialogues got loud applause from the audience who were otherwise totally focused on the court martial proceedings.

Alam through his dialogue delivery and emoting made Nawaz’s personality come through in all its dimensions while Mathur’s Desai delivered an astounding performance.

Playing a 68-year-old who despite his failing health passionately defended the act of his countrymen, Mathur, conveyed all this through his gait, slow movements, hard breathing and taking a break to sit down during the proceedings. The fire in Desai, an acclaimed lawyer, came across in Mathur’s dialogues.

Lambasting the British, he accuses them of dragging India into World Wars of their making saying that Europe’s problems become world problems, reminding many of S. Jaishankar, India’s External Affairs Minister’s interview where he had a correspondent tongue-tied by this argument.