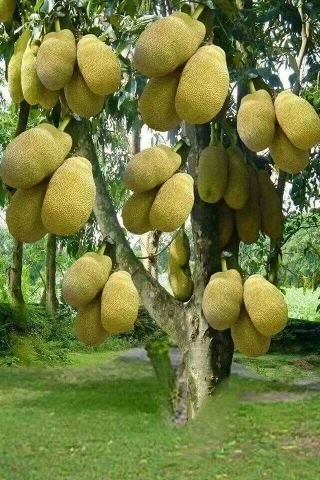

Jackfruit or Kathal binds Indian and Indonesia culinary cultures

Mango and jackfruit are both indigenous to the Indian subcontinent. In our home in Lucknow, the two marked the beginning of long, hot holidays, when the solstice and monsoons were still a few weeks away and sweltering afternoons were best spent napping, chatting, or going through unhurried lunches.

If the choicest mango was the Dussehri, that arrived rather later than expensive alphonso from Ratnagiri, or the slightly tart langda from Benares, the variety of tender jackfruit to scout the market for was kathli– small jackfruit with virtually no seeds, the best to make into a subzi with onions and whole spices, do piyazah style.

Mrs. Singh, who stayed in a large Colonial era house in the neighbourhood, had a tree growing wild in the overrun back gardens. Sometimes, tender fruit from this tree would make its way to our home, to be painstakingly peeled (after applying oil to the hands so that the sap didn’t stick) and cut into cubes. We were unaware as children that in many parts of the country, in Kerala and Bengal for instance, jackfruit was in fact a stringy ripe fruit eaten sweet, almost like a fig. Or, of jackfruit’s long history in the Subcontinent.

According to historian KT Achaya, jackfruit was called panasa in the Munda language of central India, pre dating Sanskrit. The ancient fruit is indigenous to tropical regions of Asia, and from the same family as figs. In India as also in south-east Asia, it continues to be eaten ripe and called by different names, including in Kerala, where “chakka” is a mainstay of the culinary culture.

Avadh’s nawabi culture, however, prized this ingredient differently. Before chefs like Indian Accent’s Manish Mehrotra put it on their menus—as “pulled jackfruit tacos”, and before “kathal biryani” acquired cult status, Kathli cooked as dum ka kathal, slowcooked with yoghurt, spices and onions, was a summer delicacy of my home and community, a Nawabi era dish cooked by families who were vegetarian (or selectively vegetarian) as a faux meat.

Kathli’s texture and neutral taste that allowed it to absorb the flavours of the masala made it suitable for this role. Zimikand or yam, available in winter around Diwali, was another ingredient that was treated to dum and bhun-na, two of Awadh’s prized cooking techniques, and similarly cooked as a delicacy – as “vegetarians ka meat”.

Today, as America and Europe move towards vegan meats made in labs, these hyper-local Asian dishes are enjoying more attention than ever before, as heritage foods with long, complex histories.

“Kathli” was in fact a particularly delicious variety from Faizabad, the erstwhile seat of the Nawabs of Lucknow. Its preparations may have been countryside dishes long before these were absorbed into the city repertoires of wealthy Hindu families of landlords and administrators, and refined.

If dum ka kathal, cooked using the Mughal technique of Dumpukht, where food is allowed to stew in its own juices.

As a dish is sealed on top with dough and slow-cooked on charcoal, and bhuna, where flavours are concentrated by letting moisture evaporate, were delicacies, so were things like kathal ki tahiri (there was no veg biryani then, rice dishes cooked with vegetables were called tahiri), the 19th century equivalent of today’s restaurantized kathal biryani, and kathal ka achar, which my maternal grandmother made, pickling unripe jackfruit with unripe mangoes, using spices like kalonji (onion seeds) and saunf (fennel), and mustard oil to ferment. Simple summer lunches could often involve just arhar dal, basmati rice and this kathal ka achar.

Many people who have never enjoyed these delicious tender jackfruit dishes, are perplexed by them. At a recent food festival when I cooked dum ka kathal, a guest seemed surprised that vegetarians in northern India should want to eat complex preparations that approximated Mughlai meat dishes. Why not just simple sautéed gourds or bhindi of Indian summers, cooked without “pretence”?

But kathli, as also dishes such as zimikand and “dhoka” (a genre of lentil based dishes that also approximate the textures of meat, and are part of hyper local cuisines of UP and Bengal) reveal an innate inventiveness that is a part of Indian gastronomy. Each time a dish is cooked, it is never quite the same. Each cook adjusts flavours, and improvises recipes unlike in other structured, codified cuisines. This inventiveness is a hallmark of Indian cooking, and it is something that we exported to other cultures influenced by India through our long medieval history.

In Indonesia, Gulai Nangka (nangka is the local word for jackfruit, gulai stands for “curry”) is a popular West Sumatran dish. Like in India, this is a mock meat dish, and the same surprise and glee associated with kathli or dum ka kathal used to accompany its serving. In south east Asia, like south and east India, jackfruit, an indigenous tropical fruit, is eaten ripe. But gulai nangka is savoury, spiced “curry” made from unripe fruit.

This dish seems Indian-inspired. So, how did the tender jackfruit delicacies of Avadhi cuisine reach Padang to become the mildly spiced coconut-ty curry?

A late 18th century English traveller to Indonesia William Marsden, who wrote and published The History of Sumatra in 1811 observes the influence of Indian dishes on the gulai of Indonesia.

“Their dishes are almost all prepared in that mode of dressing to which we have given the name curry (from a Hindostanic word), and which is now universally known in Europe. It is called in the Malay language gulei. , and may be composed of any kind of edible, but generally of flesh or fowl, with a variety of pulses and succulent herbage, stewed down with certain ingredients…These ingredients are, among others, the cayenne or chilli pepper, turmeric, lemon grass, cardamums, garlick, and the pulp of coconut bruised to a milk resembling that of almonds…”

Portuguese presence in Malacca and South East Asia had already introduced chillies instead of black pepper from India that had been introduced earlier to the Sumatrans along with other spices like coriander. And the substitution of coconut milk for curd that the milk-rich Indo gangetic cultures had occurred even in India, as Mughlai influences spread south. The south Indian “kurma” is a spin off of the northern qorma, itself a refining of the dopiyzah and other stews in the later Mughal period.

The Mughlai qorma, silken and thicker than the watery stewed home style qaliya dishes of Shah Jahan’s kitchen and before, were inventions influenced by Persian tastes—as we can see from the use of almonds and a sweet and sour taste profile that resulted from the use of dried fruit in the rich gravies. The Mughlai qorma had a mild taste, no fiery spices were used but it was aromatic.

This later Mughlai influence is evident in gulei, where the spices are mild, an a silken texture is achieved with coconut milk, while using highly aromatic but not pungent ingredients like cardamom.

West Sumatra in fact has had historic ties with India. Aceh, on the north west tip of Indonesia, is mentioned by Abul Fazal (Akbar’s wazir) in the Akbarnama, and trade and literary ties existed between the Aceh sultanate and the Mughal empire since the 16th century. These trade and travel routes passed via the strait of Malacca. The sultan of Aceh captured Malacca from the Portuguese in 1568 that brought trade between the Mughal empire and Achenese closer, while spices from Indonesia came to India, textiles from Indian ports in Bengal went east.

By the early 18th century, the nawabs of Bengal, who like the nawabs of Avadh were initially subsidiaries of the Mughals in Delhi, had become increasingly independent, controlling the richest province in India then. Cultural, trade and travel links that connected Delhi, Lucknow, Murshidabad, Malay and Aceh seem to have brought to the latter a quintessentially later Mughlai technique of braising followed by bhun-na, or slowly stir frying to concentrate flavours.

The Rendang is a west Sumatran dish where meat is braised in coconut milk and spices is then slowly bhunoed till the liquids have dried and the meat is dark and tender. This is exactly the same as a family of dishes in the Indian subcontinent, where bhun-na as a technique was added to the Mughlai braised dishes to give us dishes such as khade masale ka bhuna meat, the kala bhuna of what is now Bangladesh and kosha mangsho of Bengal.

Kathli slow cooked on dum with yoghut and aromatic spices, seems to have followed a similar route—via Bengal, where a similar dish exists, to south east Asia; a vegetarian version of a later Mughal braise, with coconut instead of curd; a vegetarian qorma or ishtew if you like!

Also Read: From Amritsar to Georgia—the humble Kulcha’s extraordinary journey to Caucasia

Political activist from Pakistan-occupied Jammu Kashmir (PoJK), Amjad Ayub Mirza, has condemned China's involvement in…

Bhutan Prime Minister Tshering Tobgay has said that he considers Prime Minister Narendra Modi as…

Prime Minister Narendra Modi met the Chief Advisor of the government of Bangladesh, Muhammad Yunus…

The Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs, chaired by the Prime Minister Narendra Modi, has approved…

Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Friday met with Bangladesh's chief advisor Muhammad Yunus for the…

Ambassador of India to Myanmar, Abhay Thakur said on Friday that under Prime Minister Narendra…