Earlier this week, inside the glamorous, prettily-lit precincts of Indian Accent, India’s top restaurant, I ate a refined version of a street dish more commonly found in small eateries of Muzaffarpur and southern Nepal.

Tash meat, as it is called, is strips of mutton (goat meat is called mutton all over India), marinated in a host of spices, the most distinctive of which is timur, the Himalayan version of the Sichuan peppercorn which produces a numbing, tingling sensation upon biting, is used with hot chillies in Mala Chinese dishes, and goes under the alternate name of triphal/teppal, in Goan and Konkani food.

But that is not the connection we will be exploring via this column.

Tash meat, as it turns out, is a progeny of a famous Iranian dish, the Tas Kabob, where lamb meat strips are layered with potatoes, carrots, onions and other Fall vegetables, flavoured with bitter orange water (or lime juice), as also pepper and Indian turmeric, stewed, and served topped with salad or on a bed of rice.

The Persian dish gets its name from Tas, a tinned copper utensil of the Safavids who ruled the culturally influential and vast Persian empire from early 16th to mid 18th centuries, in which the dish was ostensibly once made.

But how did this Safavid dish come to be a bazaar snack of modern day Bihar? Chef Manish Mehrotra of Indian Accent, a Bihari from Patna, serves the delicious spicy semi-dry meat atop a sattu roti; turning two common man’s dishes of his home state on their heads. The tash meat in small town Bihar or Nepal is served atop even humbler fare—on a bed of puffed or beaten rice or bhunja (as roasted chewda is called) in Bihar.

The Indian street dish is very different from the Persian one in its flavours, technique of cooking and spicing though both use thinly sliced meat and not cubes. Unlike the Persian stew, in Muzafarrpur and Champaran these slices are marinated in spices and bhunoed (shallow fried) on a hot tawa in mustard oil.

In Bihar, another form of Indianised (closer to Persian origin) Tash kebab also exists simultaneously as a Ramzan meal, now remembered by just a few families. Author Rana Safvi lists a recipe by Mrs Sakina Husain from Bihar of this dish where lightly marinated meat is boiled– and then fried, and layered with fried onions, potatoes and tomatoes, reminiscent of Iran. This of course seems like an obvious Persian influence on the erstwhile Muslim aristocracy of northern India (the Nawabs of Avadh, with roots in Nisapur, did patronise Persian arts, artists, craftsmen and cooks). But the other Tash meat, the robust street dish, displays a decidedly Indian turn towards a technique of cooking found nowhere else in the world– bhun-na.

Stir frying or controlled browning to concentrate flavours is how we would describe it in English and yet these are not exact descriptions of the “noble art” as author Pratibha Karan, a Hyderabadi hobby cook and wife of “Raja” Vijay Karan, former IPS officer, calls bhun-na in her Hyderabadi cookbook, “A Princely Legacy”.

This is one Cook book that I greatly appreciate for the simplicity and home style recipes. The author Pratibha Karan is a Bureaucrat and a vegetarian but all the recipes that I have tried have turned out fabulous. ( I am a vegetarian too that cooks meat for family) pic.twitter.com/yvl0MEYVjB

— shruti (@artyshruti) October 27, 2020

In the 19th century, as old feudal legacies were crumbling, and other Indian power centres replacing the Mughals and their subsidiaries, bhun-na seems to have emerged as a technique in Avadh, where food influences from the Mughlai kitchen, the Iranian or even the French (have you ever thought of the similarity between pate and a galauti kebab) and the English merged with influences from the countryside. In fact, the cosmopolitan culture-scape of Lucknow was contributed to equally by the land-owning Hindu rajas who first served the Nawabs and later the English with their seats of power in the countryside, and the professional Hindu classes of the Kashmiri pundits, Kayasths and Khatris as the Nawabi aristocrats.

Bhun-na was a product of this confluence—borrowing pretty obviously from the ancient Indian cooking techniques of frying and shallow frying, important to the Subcontinental kitchens as opposed to central Asia with its broiling and baking.

Beyond the Mughal qormas (creamy, mildly spiced) and qaliyas (thin gravies using yakhni or stock initially), Avadhi and later day Mughlai cuisine developed an interesting genre of the salan. The word salan in fact does not have roots in Arabic or Persian and is only known to Urdu speakers of the Indo-Gangetic plain and Hyderabad. Meat and vegetables (anything from fried colocasia to potatoes; a new crop during Warren Hastings’ time) are bhuno-ed usually in an onion gravy or masala, or even as dry or semi dry preparations. Bhuna meat or aloo-gosht salan were thus likely mid to late 19th century dishes with more spicing and frying than in the early Mughal dishes.

Small town dishes such as Tash meat fall in this genre. “Tash meat in fact is nothing other than bhuna meat in mustard oil and with spices from the lower Himalayas such as timur,” points out chef Manish Mehrotra. In fact, the dish is uncannily similar to the famous Bengali dish Kosha Mangsho, as also to the various “bhuna meats” of UP and Punjab, as well as Laal Maans of Udaipur royalty (a relatively recent invention of the early 20th century, contrary to what most people believe.)

Interestingly, Kosha Mangsho too became popular in Calcutta only in the 1920s, when it was served at Golbari, Shyambazar, at a restaurant set up not by a Bengali but a Punjabi, who may have brought the “bhuna” tradition east. Bhuna meat —call it by any name—in fact has travelled to another unexpected location too: Jamaica.

Curry Goat is Jamaica’s national dish, made on special occasions like weddings and feasts with a lot of pride. Watch a video of it being cooked and you realise how similar it is to aloo-gosht salan, or in fact kosha mangsho and Tash meat, notwithstanding its different cut of meat. Spices from the Caribbean replace those from the terai, and the rest of the Subcontinent. What is the connection?

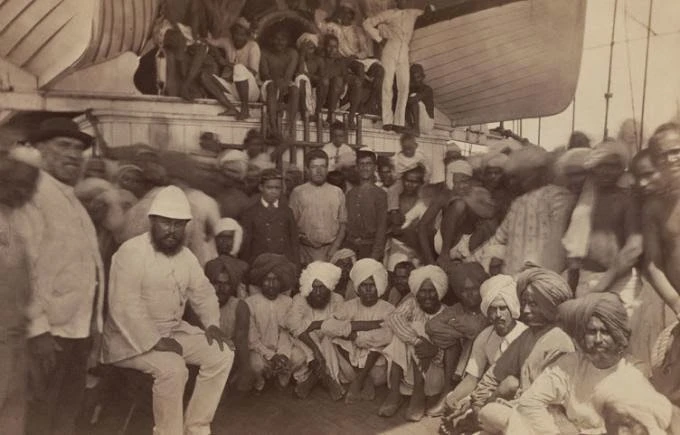

Between 1845 and 1917, right in the midst of this tumultuous time when the old Mughal feudal order was collapsing and newer tastes emerging, more than 36,000 indentured labourers (or “coolies” as they would be derisively called) went to the West Indies from Bhojpur and Awadh primarily.

They were paid less than the former African slaves by plantation owners and many converted from Hinduism or Islam to Christianity, eventually intermarrying with other interracial communities. Their memories however abide in “curry goat” made in a cauldron fairly similar to a karahi (in which kosha mangsho is bhunoed).

The dish is spiced with the Jamaican allspice (with aroma of cloves, cinnamon and nutmeg, all part of Indian garam masala), which looks very similar to the Himalayan timur of Tash meat, and the native Scotch Bonnet Peppers (instead of say the red mathania chillies that replace pepper in laal maans). Like Indian dishes, there is a long marination in vinegar, spices, ginger garlic and onions, and finally the long cooking involves painstaking “bhunoing” in a way most Indians would immediately recognise.

It is served with pea-rice (actually, kidney beans or rajma with rice), which may be a throwback to the old Avadhi tradition of serving salan with green peas-rice, a common accompaniment to the gravies.

In the end, call it Tash or Bhuna or Kosha, it is a dish that has travelled more than half the world.

Also Read: How colonial Britain bungled in viewing diverse Indian cuisine as a mere ‘curry’