Life can be as bewildering as death. A sudden cataclysmic event, its origins wrapped in some game of dice beyond one’s imagination, with consequences beyond one’s control, can whirl you out of every possible preconception, throwing you into the unknown.

Mohammed Yusuf Khan was 28 years old when India was partitioned in 1947, and his birthplace, Peshawar, became part of Muslim Pakistan. His father, Lala Ghulam Sarwar Khan, a fruit merchant with orchards in Peshawar, had brought the family to Maharashtra only in the 1930s. He used the prefix ‘Lala’ proudly, for it was signature evidence of the remarkable secular harmony of India’s North West Frontier.

But politics had begun to poison this syncretic society. It is schoolboy knowledge that the British introduced railways into India. Regrettably, our schoolboys are still not taught that the British injected communalism through the railways. While travelling on the Frontier Mail the teenager Yusuf heard cries from platform vendors selling “Hindu chai” and “Muslim chai”, while water taps were labelled, from Peshawar to Dhaka, “Hindu paani” and “Muslim paani”.

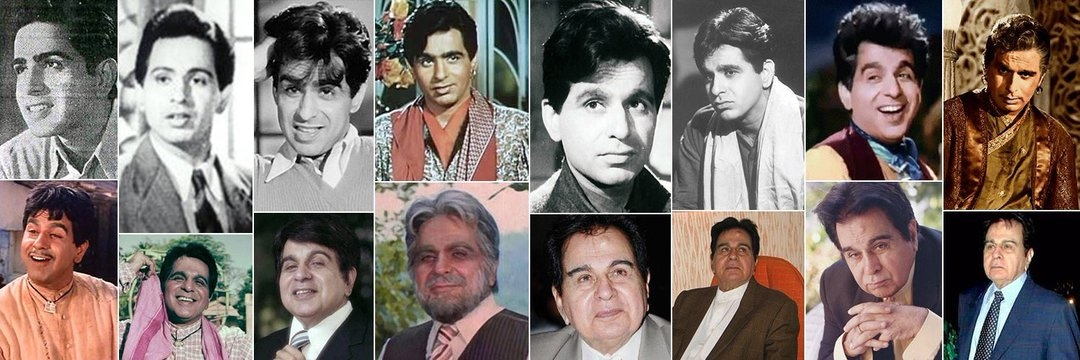

As a youngster Yusuf tried a few jobs, but nothing worked until he met the fabled actress Devika Rani and her husband Himanshu Rai, owner of Bombay Talkies. Pleasantly startled by his looks, diction, gait and visible talent, they offered him a career in the still nascent film industry. Devika Rani suggested that he acquire a screen name from a selection she had made. Yusuf chose ‘Dilip Kumar’.

His first film, Jwar Bhata, was a flop. He would not become a household name until the release of the memorable Andaaz in 1949, in which he acted with his Peshawar-born friend Raj Kapoor. In 1947, there was no certainty that Yusuf Khan would become a legend called Dilip Kumar. Partition gave him with a choice. Pakistan’s film industry was eager for talent.

In 1947 Mohammad Yusuf Khan chose India over Pakistan because, like countless other Muslims, he believed in the multi-cultural genius of a secular society rather than the mental confines of single-faith land.

The First Khan of Mumbai’s brilliant film industry was also a First Patriot of India.

Seven decades after freedom, we must not underestimate the pressures of 1947. The country was aflame with deliberately engineered riots, and Mumbai was as volatile as any other urban conglomeration with a heavily mixed population. Pakistan had been sold to the community as some sort of dreamland. The thought of migration would be only natural for a young man born in Peshawar, speaking the charming dialect of the Frontier called Hindko. Dilip Kumar’s decision to remain an Indian was a triumph of conviction and ideology over ephemeral temptation.

Dilip Kumar did not have much of a feel for politics, although he was elected to the Rajya Sabha by the Congress. But he had a deep commitment to India, built on the fundamental pillars of secularism, equality, religious freedom and democracy.

Three Khans of the last three decades, Shahrukh, Aamir and Salman, have never felt the need to adopt a screen name. Indians, who keep the film industry alive by buying its products, have risen far above the hesitant constraints of the 1940s. The difference is this. Yusuf Khan became Dilip Kumar in British India. Shahrukh, Aamir and Salman were born in Indian India.

Dilip Kumar was the first winner of a Filmfare award for male actors, and the first thespian who received Rs 100,000 as fees for a film. He might have become an international star if he had accepted David Lean’s offer of a role in Lawrence of Arabia, which eventually went to Egypt’s Omar Sharif. The only quarrel I have with his reputation is the tag of “Tragedy King”. Anyone who has seen Azaad and Kohinoor knows that his brilliance was not limited to a single dimension.

(MJ Akbar is an MP and the author of, most recently, Gandhi’s Hinduism: The Struggle against Jinnah’s Islam)