Farahnaz Ispahani’s book, “Purifying the Land of the Pure”, offers a unique study on the current political-social scenario in the neighboring Pakistan. In 1947, Pakistan and India were born as twins when the British Parliament enacted the India Independence Act paving the way for two countries.

The legislation was passed before the colonial power wrapped up its establishment for a smooth transfer of power in the undivided India. Ispahani’s book is a well-researched document on the plight of the minorities in Pakistan, mostly Hindus, Sikhs and Christians, and the non-Wahabi Islamic sects like Shias, Ahmadis and the Sufis. She, however, does not tell why the Sunni Muslims of Bengal, and the Mohajirs, were alienated from the Pakistani establishment or the ruling elite comprising the army, its intelligence wing, Inter Service Intelligence (ISI) and the aggressive Muslim clergy.

The repression of Hindus and Sikhs, opposed to the partition, could be explained, but sidelining of Bengali Muslims, Mohajirs (UP Muslims), Shias, Ahmadis and Christians who were at the forefront needs to be further studied. The book offers an in-depth narrative of a Muslim land dreamt by a galaxy of Muslim elites comprising members of academia, western educated professionals and landlords. It gives us the narrative of a new power elite emerging during the post-1947 era.

The book does not explain why only Sunni Muslims of Bengal and Mohajirs accepted that the two-nation theory was a mistake. The Mohajirs are openly working for a united India from Britain, Canada and other places. On the other hand, the Shias, Ahmadis and Pakistani Christians continue to support the sectarian politics of the contemporary Pakistan. Ahmadis were officially declared non-Muslims by an amendment in the Pakistani constitution in 1974.

In spite of almost half-a-century of repression, they refuse to disown the philosophy of Pakistan. In this 271-page book, the author has repeatedly stated that the founder of Pakistan Muhammed Ali Jinnah was keen to have a secular state based on the ideals of Islam. It is a self-contradictory approach. Jinnah was a non-conformist Muslim working against the concept of a secular state. In a secular state, the religion has little role in the affairs of the state. But Pakistan is an attempt to deny and bury the traditional 5000-year ancient civilization which blossomed in the region under the pretext of promoting the monotheistic belief in one god – that of the Wahabi denomination. The Christians too were seen officially aligning with Jinnah before independence. It was not surprising that most of the Christians were the local converts who had changed their religion for seeking favors of the colonial masters.

In 1942, the All India Christian Association had supported the two-nation theory of Jinnah. It may also be noted that, in spite of widespread violence against Christians in Pakistan, the Church leaders in India are rallying against Citizenship Amendment Act. Before Independence too, prominent Christians writers and authors used to regularly write in favor of a Muslim homeland. Even after 1947, a Christian journalist-turned-priest lied to the US Congress about the alleged harassment of his community in India.

Therefore, the author should have explained the sectarian role of the so-called minorities too. The book offers a detailed narrative of the plight of the so-called liberal and progressive political elements. They, however, never officially opposed the two-nation theory. The Pakistan People’s Party and its founder, Z.A. Bhutto, had indulged in this “illogical” game. Since the author was elected to the Pakistan National Assembly on the ticket of People’s Party, she could not be much critical of Bhutto’s opportunistic approach to politics. But as an author and researcher, she needs to shed off the personal concerns.

Bhutto was a favorite of Ayub Khan, the military dictator, and his political career blossomed under the army establishment. If only he had supported Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who had won majority in the Pakistan National Assembly, the genocide in Bengal could have been averted. The author’s observation that in India democracy has flourished is partly true. In the present day India, democratic institutions are under pressure due to various facets of the sectarian politics.

In Pakistan, a pure Islamic regime could have ushered in all-inclusive democracy but it was hijacked by a ruling mafia comprising army, Muslim clergy having the support of the West and now China. In spite of promoting ties with the Middle-East countries, Zia-ul-Haq, the army chief, toppled Bhutto’s elected civilian government and got him hanged through a manipulated judicial trial. Zia used Islam to legitimize his dictatorship and introduced massive training for terrorists to serve the Western interests in the region.

The author of the book is also an irrepressible activist. She successfully exposes the inadequacies, narrow vision and failures of the rulers of Pakistan. She joins the elite group of intellectuals and authors in Pakistan such as Hassan Nissar and Najam Sethi for having a common vision for the people of Indian sub-continent. However, she does not explain why the Christians and the Muslims sects still expect justice in Pakistan.

The readers would perhaps have to now wait for another book from her to tell us that why Muslim elite of the undivided India had joined Jinnah, a non-conformist Muslim, and debunked an Islamic scholar, Maulana Abdul Kalam Azad, who was opposed to the partition of India. The problems of India and Pakistan cannot be resolved unless intellectuals like her adopt a much more comprehensive approach. It could be a sequel to the book on India’s partition by Wali Khan, son of the legendary Frontier Gandhi, Abdul Gaffar Khan, ‘Facts are facts: The untold story of India's partition Unknown Binding.’ It was published in 1987 and continues to be relevant even 33 years after its publication. It is not only the minorities which are being repressed. The Wahabi Sunni community too is being ignored because Pakistan’s ruling mafia only talks about the Riasat-e-Medina or a welfare state though in reality it is an anti-people, insensitive group which has cleverly hijacked Islam for its political gains.

Ispahani rightly bemoans, “My grandfather supported the idea of Pakistan, but he never imagined a life there.” Her grandfather, Mirza Abul Hassan Ispahani, had moved the resolution at the 1942 session of Muslim League held in Allahabad in Uttar Pradesh, giving full powers to Muhammed Ali Jinnah, also a Shia, "to take every step or action as he may consider necessary in furtherance of relating to the objects of the Muslim League as he deems proper.”

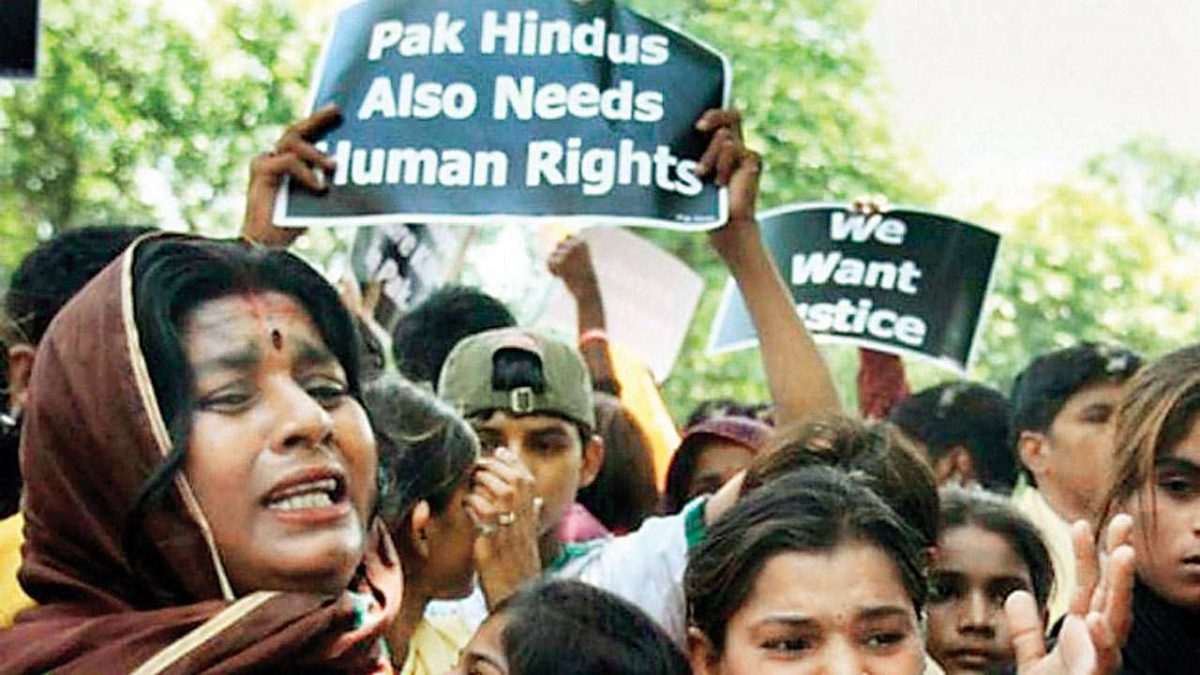

The resolution paved the way to enroll the common Muslims, mostly Sunnis, to be mobilized for a separate homeland. At the time of partition, almost 23 percent of Pakistan’s population comprised of non-Muslim citizens. Today, the proportion of non-Muslims has declined to approximately three percent. The Shias, who account almost 20 per cent population of the country, are now being targeted. The anti-Shia militants roam with impunity, appear on prime-time talk shows on television and hold political rallies where they declare Shias as unbelievers and Wajib-ul-Qatal (deserving of death). In 2013, a large number of Hazara Shias in Quetta were killed.

Similarly, the Christians of Lahore, who had enthusiastically supported Pakistan in 1947, are facing mob attacks and huge discrimination. The book rightly doubts the future of Pakistan due to the rising radicalization of Pakistani society. The government officials and politicians deliberately disregard the rights of minorities and are also unwilling to confront the Islamist extremists. The policy of Pakistan’s security services, mainly ISI, to use religious extremists in regional battlegrounds such as Kashmir and Afghanistan also contributes to their impunity.

There has also been a steady elimination of anyone who opposes this Islamist narrative, including Benazir Bhutto, Salmaan Taseer, Shahbaz Bhatti and others. The author pleads that it is in the interest of Pakistan’s neighbors and the international community to support the minority communities in Pakistan and to support the voices of those Pakistanis who refuse to give up the idea of a pluralist society. However, she forgets that the Muslim minority sects and Christians are still supporting the concept of Pakistan. Bangladesh could get Indian and international support because its leadership rejected the two-nation theory.