While there is an extensive and heated debate in today’s world over what is an ideal diet for humankind – vegetarian, non-vegetarian or even vegan, the Palaeolithic food was not all green as per a report in sciencedaily.com.

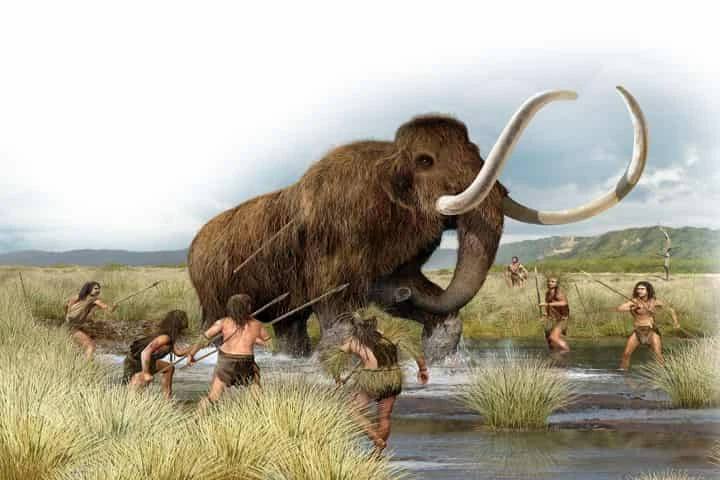

According to a study published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology human beings were the top predator for about 2 million years. It was only with the extinction of the big and mega animals — mammoths, mastodons, and giant sloths — in different parts of the world and decrease in the animal food supplies towards the end Stone Age did the content of vegetables in human diet increase. They ultimately started to cultivate plants and raise animals – thereby becoming farmers.

The writers of this paper were Dr. Miki Ben-Dor and Prof. Ran Barkai from Tel Aviv University’s Jacob M. Alkov Department of Archaeology and Raphael Sirtoli of Portugal.

Speaking about the food habits of people of Stone Age, Ben-Dor observed: "So far, attempts to reconstruct the diet of stone-age humans were mostly based on comparisons to 20th Century hunter-gatherer societies.”

Explaining how this was not accurate he said: "This comparison is futile, however, because two million years ago hunter-gatherer societies could hunt and consume elephants and other large animals — while today's hunter gatherers do not have access to such bounty. The entire ecosystem has changed, and conditions cannot be compared. We decided to use other methods to reconstruct the diet of stone-age humans: to examine the memory preserved in our own bodies, our metabolism, genetics and physical build. Human behaviour changes rapidly, but evolution is slow. The body remembers."

The researchers went on to collect 25 lines of evidence after going through 400 scientific papers concerning varied streams of science while they concentrated on the central point – were the human beings of Stone Age specialised carnivores or generalist omnivores? The evidence collected came predominantly from current biology research, namely, metabolism, genetics, morphology and physiology.

Talking about this aspect, Ben-Dor said: "One prominent example is the acidity of the human stomach. The acidity in our stomach is high when compared to omnivores and even to other predators. Producing and maintaining strong acidity require large amounts of energy, and its existence is evidence for consuming animal products. Strong acidity provides protection from harmful bacteria found in meat, and prehistoric humans, hunting large animals whose meat sufficed for days or even weeks, often consumed old meat containing large quantities of bacteria, and thus needed to maintain a high level of acidity.”

Highlighting another vital facet of the study, Ben-Dor added: “Another indication of being predators is the structure of the fat cells in our bodies. In the bodies of omnivores, fat is stored in a relatively small number of large fat cells, while in predators, including humans, it's the other way around: we have a much larger number of smaller fat cells.”

Likewise, our genes also point in the direction of predation. Geneticists have drawn the conclusion that "areas of the human genome were closed off to enable a fat-rich diet, while in chimpanzees, areas of the genome were opened to enable a sugar-rich diet."

Going beyond the biology of human beings, there is proof available from archaeology too. Examining the stable isotopes of prehistoric human bones and the stalking and killing style of ancient people, point to the direction that hunters preferred and specialised to hunt animals which were large and medium in size and had high content of fat.

This is further collaborated by looking at present-day big predators who get more than 70 per cent of the energy needs from animal sources. This reinforces that humans hunted large animals and were hypercarnivores.

For humans hunting formed an essential part of life and evidence of large animal remains from several archaeological sites proves that. “Most probably, like in current-day predators, hunting itself was a focal human activity throughout most of human evolution. Other archaeological evidence — like the fact that specialized tools for obtaining and processing vegetable foods only appeared in the later stages of human evolution — also supports the centrality of large animals in the human diet, throughout most of human history,” remarked Ben-Dor.

The study has far-reaching implications as it suggested an alternate paradigm for understanding the evolution of human beings. Instead of the prevailing and widely held theory that people evolved and survived thanks to the pliability in their dietary habits which integrated meat and vegetables, the research proposed humankind evolved as predators of large animals.

The stone-age people also ate plants. “But according to the findings of this study plants only became a major component of the human diet toward the end of the era,” informed Ben-Dor.

Alteration in genes and advent of tools made of stone which were specifically used for plant processing led the scientists to deduce that 85,000 years ago in Africa and 40,000 years ago in Europe and Asia, there was a slow increase of plant foods in the diet. This depended on the diverse conditions of the ecology.

This also gave rise to a distinct stone tool culture which was local in character. This stands out in comparison to the two million years when humans were the top predator as stone tools were same irrespective of what the local conditions of the ecology were.