Regardless of whether you are still buying tomatoes, switching to purees which contain just around 40 per cent of the fruit, or ruing the price rise, fact is that the not-so-humble tomato is a relatively recent entrant into kitchens not just in India but globally.

Like its cousin, the potato (both belong to the solanaceae family), the tomato is indigenous to Peru and Ecuador, and was eaten by the Aztecs in around 700 AD, who called it tomatl (Smithsonian magazine). The earliest wild varieties of the tomato were cherry tomatoes but by the time the Spanish found the plant growing in Mexico, it was being cultivated in Mesoamerica in several regions. The Spanish brought back seeds of this plant, belonging to the nightshade family to which aubergines and peppers belong too as well as several poisonous species, by the early 16th century. But for the next 200 years, the tomato would have a chequered career in Europe before finding largescale acceptance in the 19th century, as the pizza was developed in Naples (in 1880) —from breads where salt was a topping not tomatoes, till the passata found big use as a pizza spread.

Surat's iconic "Tameta Bhajiya" combines crispiness and tanginess that is loved by all. The famous street food is made with thick, deep-fried tomato slices, layered with spicy chutney, and dipped into chickpea batter, creating a delicious snack. #GujaratiFood @InfoGujarat pic.twitter.com/K0RUBaQMrH

— Parimal Nathwani (@mpparimal) July 27, 2023

Early references in Europe referred to the tomato as a golden apple or a love apple, after herbalists deemed it an aphrodisiac akin to the mandrake —the root of the mandrake famously was used in purported witchcraft to cast spells and Shakespeare’s the Three Sister’s reference the myth in Macbeth in their chants.

Tomato’s many names in southern Europe reference these origins. In France, it is still called pomme d’amour or “love apple”, though the name may also have been a corruption of the Spanish poma de moros (“fruit of the Moors”, referring to the tomato’s earliest habitat of cultivation in southern Europe, with Anadulcia being ruled by the “moors” or the Muslim tribes of north Africa rulers till late 15th century). In Italian, as also on many European menus that you may still encounter, the tomato is the pomodoro, or the golden apple, though it is contended that this too may be a corruption of the Spanish term.

In any case, post its advent from Mexico in the early 16th century to Spain, and its consequent spread to other parts of Europe, the tomato inspired curiosity but not necessarily love, as it acquired a reputation as being either a fruit of temptation similar to the Biblical apple or poisonous. Until the early 19th century, in northern Europe, the tomato was used only for ornamental purposes, some agriculturists and herbalists have not just wrongly attributed poisonous properties to the fruit but also spread the myth that it was to be used in foods of hotter parts of the world and would disagree with digestion in colder northern terrain.

There was another cause for tomato’s bad reputation: Many rich people died after consuming cooked tomatoes. It was later found that lead poisoning was to blame since the rich in Europe at that time used pewter (an alloy of copper, tin and lead) plates, high in lead content. The acidity of the tomatoes would result in lead leeching into the food and causing the deaths. Poor people, who did not eat off pewter and could not afford it remained healthy after consuming raw tomatoes.

For two hundred years, medieval Europe’s wealthy thus eschewed tomato – ironical, given the fact that the use of tomatoes in Indian cooking, stems from colonial practices!

#FoodHistory Butter chicken is a popular Indian dish made with marinated chicken cooked in a tomato-based sauce. It is said to have originated in the 1950s in Delhi, India, at a restaurant called Moti Mahal. The dish initially was created by adding butter and tomato …cont pic.twitter.com/vZeoiPTsRD

— jeffreysHistory (@jeffreysHistory) April 14, 2023

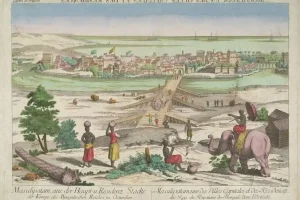

How did the tomato reach India? It is likely that the Portuguese got it to India, via Goa or colonies on the east coast. But tomato was hardly used in regional Indian cooking of the Mughal era. Indian cooking has traditionally had the idea of a sour ingredient added to almost all gravies to balance the flavours, in keeping with the philosophy of aesthetics and arts, where the navrasas evoke different emotional response, as well as Ayurveda with a similar emphasis on the rasas and doshas of each ingredients, properties which must be balanced in food cooked according to seasonality as also for specific body “types”.

Mughal cooking meanwhile, highly influenced by Persian tastes, also included sours to produce a sweet-sour taste in dishes. But if you examine medieval Indian recipes from the 18th or even 19th centuries, you will find tomato hardly being used in most of the dishes, whether courtly or “common”.

The souring agent for rich Mughlai dishes in the north was yoghurt—incorporated into the imperial kitchens no doubt as an influence from the Doab cooking practices—where milk and milk products are prized and made use of, the region being abundant in cattle wealth. Persian influences meant that piquant fruit too started being used in meat gravies (and later other vegetarian ones too). The use of dried pomegranate seeds or anardana in Delhi, UP and Punjab or the use of plums in qormas is a direct result of the Iranian influence.

If you look at the food of old Delhi, you will find anardana used as a sour not just in chutneys (methi and anardana) and potato gravies scooped up with bedmi but also in later day Punjabi dishes such as chole, where anardana lends the requiste piquancy to the hearty breakfast dish.

In Rajasthan, Haryana and west, kachri, a local cucumber like fruit was used as a souring agent cum tenderizer. Kachri in fact still grows wild in these regions. And in other parts of eastern, southern and central and coastal India, we have had everything from tamarind to kokum souring fish and meats, not to mention unripe mango, used both fresh and in dried forms. The use of vinegar is also a European/Portuguese influence on Indian food, and you find Goan dishes with a Portuguese lineage use that, whereas the Saraswats did not traditionally use vinegar.

The use of tomatoes seems to have caught on in India, with other “English vegetables”, first as an ingredient used by the British and Anglo-Indian communities and then by others as cultivation was promoted in parts of India.

In India, Maharashtra, Karnataka and Andhra cultivate the most tomatoes. And since it began as a local ingredient before 24 X & availability and wide reach, dishes such as the saar in Maharashtra and the kutt in Andhra/Telangana replaced older sours with tomatoes as the main ingredients. It is a mistake to think of the tomato as an exclusively Punjabi phenomenon—even though its most famous dish is possibly the butter chicken, created as a fix to use up leftover drying tandoori chicken and as a popular inexpensive dish to cater to the masses post partition in Delhi. As tomatoes replaced the rich milk and curd-based Mughlai cooking, it was an attempt at democratising taste—the burst of umami tomatoes provided along with sourness contributed undoubtedly to butter chicken emerging as a popular and massy restaurant dish.

No one would have thought then how the tables would turn. Restaurants may be struggling just now to cook up your makhni gravy while still keeping their food costs down.